Announcement

Use this area to highlight news, Announcements, and Featured Items by using the blog feature

Use this area to highlight news, Announcements, and Featured Items by using the blog feature

One of the things we love about the ITK tools is how adaptable they are. Each one is lovingly crafted to be easy to use across a wide range of situations… but they are also designed to be modified to meet the unique needs and situations of individual users. We sincerely love it when people take these tools and change them. And we love it even MORE when they share their new creations with us!

A group we’re working with recently did exactly that with one of our favorite tools the Problem Framing Canvas. The result was a Simplified Problem Framing Canvas that we just had to share with the rest of you.

It has all the magic and impact of the original, but in a more focused and tighter structure. I just might like it better than our original one (and that’s really saying something).

Today’s blog post is by Aaditi Padhi, one of the talented high school interns who worked with Team Toolkit this summer. We were delighted to have her on the team and are glad she’s sharing her story and experiences in this post!

Does this blog’s title question sound familiar? I’m sure many of you can relate to the anxiety of doing something wrong or the uncertainty of trying something new. This is a question I asked myself more times than I could count throughout my internship. Most of my experience as a high school intern in the ITK team was smooth sailing, but at times, it was clouded by uncertainty and a fear of failure. Some of the most important lessons I learned this summer were to embrace that fear and to keep persisting because not every problem has a crystal–clear solution (cliché, I know). However, these lessons also translate into advice for those of you using the ITK. So, from my summer stories to your creative journey as a reader, here are my top tips for innovating smart, not right.

An Intern’s Guide to Continuous Improvement:

Whether it’s working through a design process or trying your hand at carpentry, it’s unlikely that you’re going to hit the nail on the head on your first try. Early on, I realized that innovating is not always about getting perfect results right away, but rather it involves looping through a process of adding, receiving feedback, and changing. Sometimes, it took me as little as one shot to conceive ideal results, but many other times, it took multiple feedback sessions until I refined a product.

Continuous improvement is a term that embodies this method – it describes the process of incremental changes over time. In this sense, using the ITK is an excellent example of this concept. It takes a handful of tools, many creative thinkers, and dozens of iterations to create a deliverable. At times, each iteration may not even bring forth improvements – but fear not, because persistence is the key to succeeding.

There are no Wrong Answers

As a preface, innovating isn’t like solving an algebra problem where there is only one correct answer. It’s a common misconception that innovation tools only involve solutions that fit a certain frame. Using a multitude of tools in the toolkit and observing ITK workshops has taught me that there are no wrong answers. The diversity of ideas that are offered is one of the most crucial parts of the design process. In fact, receiving a wide variety of answers, whether they align with the traditional path or not per se, can be useful in other ways. Countless times have I proposed an idea that seemed insignificant or irrelevant at the time, but later came in handy later since I could recycle or repurpose them. It’s true that an idea may not be the most viable or appealing, but sometimes, it is better to keep it to the side than deem it worthless. Remember, when in doubt, write it down!

Don’t Be Afraid to Fail

It took a failed startup and multiple downfalls for Bill Gates to start Microsoft. Arianna Huffington was rejected by 37 publishers before her publication rose to fame as the Huffington Post empire. Steve Jobs was even fired from a company he founded before he came back to help push Apple to success. In an era of exploration, one of the most important things to remember is that failure cultivates success. One of the reasons I was so close-minded at the beginning of my internship when I only focused on doing things the “right” way, was my fear of failure. However, as I got comfortable with the design process, I also got comfortable with pushing my boundaries and accepting the fact that it’s ok to fail. Having a fear of failing will only limit the ideas you produce, but welcoming failure as a reality gives you the freedom to think beyond the scope of ‘conventional’.

Hopefully, these tips will inspire you to dive into an ocean of innovation. It is, admittedly, an intimidating notion, but it takes time, hardships, and failures to drive towards success. To quote Babe Ruth, “Never let the fear of striking out keep you from playing the game.”

We all used to have in-person meetings for collaboration and ideation activities. Then COVID-19 hit. And quarantine. And we all scrambled to maintain collaborations across stakeholders despite the inability to continue in the usual ways. And as you no doubt have noticed, there are critical differences between planning and executing a successful virtual collaboration and the traditional in-person events. It’s not as easy as just doing the same old stuff, but this time on video. We have to make a whole bunch of other changes, and they aren’t easy or obvious. That’s precisely where we’d like to help.

We all used to have in-person meetings for collaboration and ideation activities. Then COVID-19 hit. And quarantine. And we all scrambled to maintain collaborations across stakeholders despite the inability to continue in the usual ways. And as you no doubt have noticed, there are critical differences between planning and executing a successful virtual collaboration and the traditional in-person events. It’s not as easy as just doing the same old stuff, but this time on video. We have to make a whole bunch of other changes, and they aren’t easy or obvious. That’s precisely where we’d like to help.

For a little background, check out Virtual Experimental Conference Delivers Real-World Results. That article basically describes an experiment we did, where a “coalition of the willing” from across MITRE’s Acquisition Disruptors (aka, the MAD Team) and the MITRE Innovation Toolkit (ITK) came together to respond to the unfortunate cancellations of the innovation collaboration events, pivoting from physical events into on-line events. We have planned and executed several events since that fateful day.

As we began reflecting on the experiences over the past few months, we took time to examine the virtual collaboration problem, which resulted in the following problem statement:

How might we create ways to continue collaborating with our Sponsors across multiple levels of classification while considering restrictions on physical proximity and the lack of accepted virtual environment norms/protocols as we aim to effectively solve problems to create a safer world?

With the help of MITRE’s Kaylee White as our lead facilitator, we ideated (ie, brainstormed) the key attributes associated with the virtual collaboration problem statement using our personal experiences and the Lotus Blossom tool from ITK. When Kaylee showed us the final product, we realized, “Hey! This is the beginning of a checklist to enable effective planning and executing of virtual collaboration events!”

And so, the “It’s Not a Checklist” Checklist was born. While it is far from a complete set of activities and considerations needed to deliver a successful virtual collaboration, it’s a pretty good starting point. We have shared the information with MITRE teammates, and received very positive feedback. So, we would like to take the sharing a step further and offer the information here for your use. The presentation is approved for release – so feel free to share away!

Are you using the Not a Checklist? Did it help? Did we miss any key items? We welcome your feedback! Please share your experiences and ideas. Thank you!

Today’s blog post is by Allison Khaw, a systems engineer and frequent creative collaborator & co-facilitator with the Innovation Toolkit.

Over the holidays, I received a Knock Knock “Make A Decision” notepad as a gift. It walks you through the decision-making process with just the right mix of realism and levity. This was a perfect gift for me, as I’ve always loved miniature versions of, well, everything. I have a mini book, a mini mirror, and a mini briefcase for business cards in a neat row on my desk, and if you look more closely, you’ll find a handful (literally) of other such knick-knacks too. In my day-to-day job as a systems engineer at MITRE, I model systems on a much larger scale, and yet, this notepad got me thinking… What if the tools in the Innovation Toolkit were represented in a similar format? In addition to the standard large format tool canvases, what if there were… Mini Canvases?

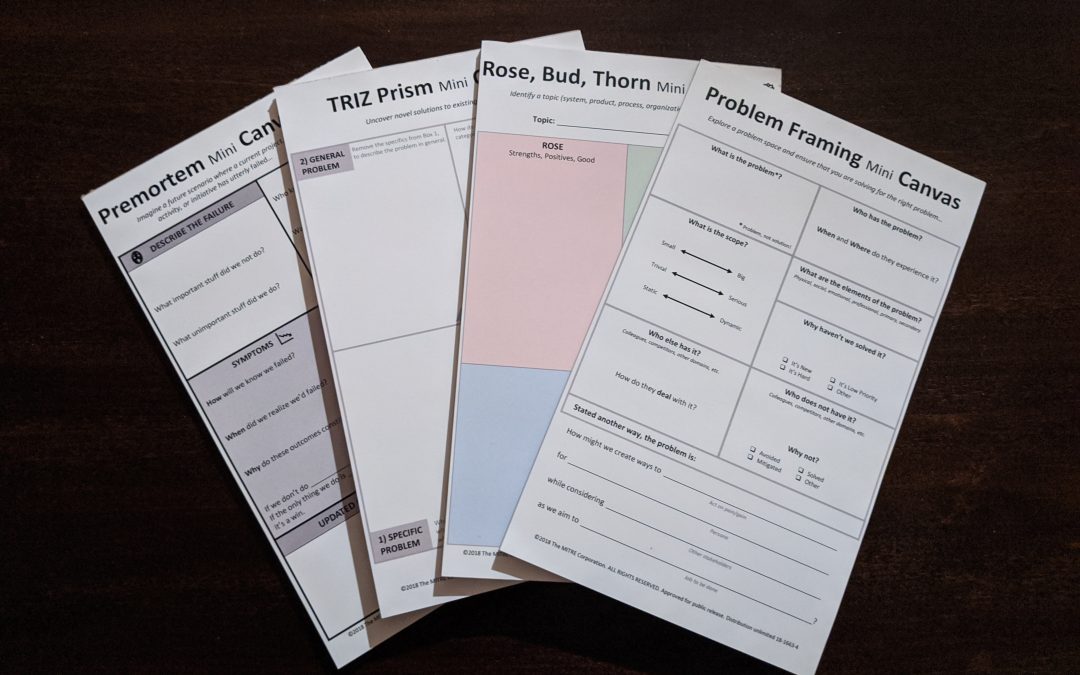

And the idea was born. Four ITK tools – Problem Framing, Premortem, TRIZ Prism, and Rose Bud Thorn – seemed perfect for a first batch. These tools could be designed to fit on 8.5×5.5” sheets of paper while remaining readable. They could then be produced in bulk and widely distributed. Through it all, their power to help would speak louder than their unassuming size…

• Need to frame a problem? Explore a problem space and ensure that you are solving for the right problem with the Problem Framing tool.

• Need to develop a plan? Imagine a future scenario where a current project, activity, or initiative has utterly failed… and explore this scenario with the Premortem tool.

• Need to generate ideas? Uncover novel solutions to existing problems with the TRIZ Prism tool.

• Need to evaluate options? Identify a topic (system, product, process, organization, etc.) for analysis with the Rose, Bud, Thorn tool.

The be auty of these Mini Canvases is that they emulate an innovative mindset. You want to experiment with using the same tool in different ways? You “fail” with your current sheet and want to begin anew? Easy, just rip off the old sheet and use a fresh one. The possibilities are endless.

auty of these Mini Canvases is that they emulate an innovative mindset. You want to experiment with using the same tool in different ways? You “fail” with your current sheet and want to begin anew? Easy, just rip off the old sheet and use a fresh one. The possibilities are endless.

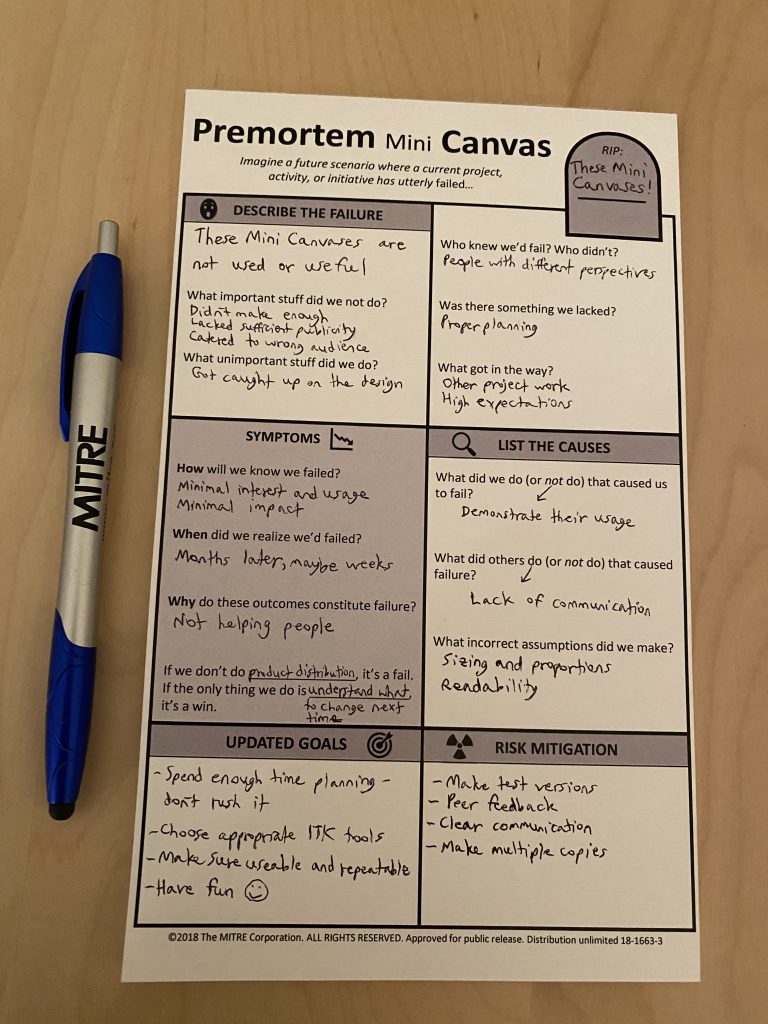

But hey, we practice what we preach. What if these Mini Canvases are not successful? Let’s find out! Here is a Premortem Mini Canvas filled out meta-style (RIP: These Mini Canvases). We’ll use what we discover here to adjust in the future. What about you? What can you change about your own goals and risk mitigation strategies to improve your current products?

Looking ahead, these Mini Canvases will be used as ITK “swag” at conferences and events (stay tuned!). They can serve as effective innovation tools, simple conversation-starters, or both. At the very least, they can sit at your desk, as a playful reminder of the tools at your disposal, if you so need them.

We plan to produce more of them soon.

I never thought that my love for everything miniature would come into play here, and yet it did. So keep an eye out. You never know when inspiration will strike and how far along the innovation path it may take you. Wherever you find yourself, Team Toolkit is ready to help.

– Allison Khaw

This week’s blog post is an interview with Dan Ward, talking about his new book Lift – Innovation Lessons From Flying Machines That ALMOST Worked and The People Who NEARLY Flew Them. As a special bonus, we’ve got a 14-minute audio version of the interview, which is (mostly) transcribed below

Dan, Lift is your third book. Your first book was titled, FIRE – How Fast, Inexpensive, Restrained, and Elegant Methods Ignite Innovation which explores how excessive investment of time, money, or complexity actually reduces innovation and that the secret to innovation is to be fast, inexpensive, simple, and restrained. Your second book digs deeper into those concepts – specifically the term Elegance. Titled, The Simplicity Cycle – A Field Guide to Making Things Better Without Making Them Worse, you show us that unnecessary complexity adds complications, then provide a number of techniques for identifying the problem and striking the proper balance. What made you want to write this book?

I came across these stories of 19th century flying machines several years ago, and they completely blew my mind. I kinda fell in love with the topic. I couldn’t stop thinking about them, and the more research I did into flying machines from the 1800’s, the more I learned, the more I wanted to share these stories with other people.

In large part that’s because most of us know so little about this era of aviation history. Even among aeronautical engineers, pilots, and Air Force personnel, there’s this weird historical blind spot. People seem to think Orville and Wilbur were the first to try to build an airplane, as if they were starting with a blank sheet of paper. Of course that’s not true. There were hundreds of people doing similar work, particularly in the late 1800’s. Their stories are amazing on their own, but the best part is they are also hugely relevant to the challenges we face today.

In your intro, you talk about the five stars of your book. In a sentence or less, how would you summarize each individual?

Ooh, that’s tough, but here goes! Chapter one is about Octave Chanute, a connector who built a community for aviation experimenters in the late 1800’s at a time when lots of people were experimenting and nobody was succeeding.

Chapter two introduces Otto Lilienthal, who bravely strapped on home-made wings and jumped off cliffs thousands of times, trying to figure out how to make an airplane stable.

Alberto Santos=Dumont is the core of Chapter three, and his persistence and iterative approach to design was a huge inspiration. Also, I want to build my own version of his airship Number 9 someday.

Chapter four is about James Means, who beautifully blended pragmatic realism with a counter-intuitive perspective on gravity, and took an inclusive and invitational posture in his work.

Finally, Octave Chanute wrote a perfect summary of Chapter five’s subject, so I’ll just quote him: “If there be one man, more than another, who deserves to succeed in flying through the air, that man is Mr. Laurence Hargrave…” That pretty much says it all.

Do you have a favorite story that you came across in your research for the book – that really resonated or inspired you?

There’s a story I adore but that didn’t include because I couldn’t quite make it fit into the book, so I’ll share it here. It’s about a guy named Moulillard who strapped on some homemade wings, jumped over a drainage ditch, and was absolutely terrified when he found himself gliding along a foot off the ground, unable to steer or land. He estimated his speed was between 8 and 11 miles per hour, which put him somewhere between the top speed of a house mouse and an alligator (yes, I looked that up).

Mouillard’s flight was scary because he was out in the back forty of his farm, and he knew that if he crashed and got injured, it would be a long time before anyone found him. Fortunately he came back to earth safely – again, he was literally one foot off the ground, traveling at the speed of a mouse – and the coolest part is that after he landed he immediately measured the distance he’d flown. What an engineer!

Incidentally, he flew 138 feet that day. That’s 18 feet further than the Wright Brother’s first flight.

I love that he was so scared (the phrase he used was “oh, the horror!”), and I love that the first thing he did after landing was measure the distance he’d covered. I hope I would do the same thing in that situation. But what’s really important about the story is that before jumping, he clearly had not anticipated what to do if his wings worked. His design was focused on producing lift, with absolutely zero mechanism for control. There’s probably a lesson in there too.

Lift is more than just stories about some men – and women – who built flying machines, but also practical insights about innovation. What do you want or hope readers take away from your book?

I think the main lesson is on page five: “failure is never the whole story, nor the end of the story.” Of course, I hope people will read the rest of the book too, but if you only read up to page five, you’ll at least have something useful to take away.

The other big point is the importance of diversity, inclusion, and collaboration. There’s a very clear pattern across all these experiments, and all the modern stories in the book as well, about the relationship between diversity and innovation. I lay it out in Chapter three, writing “…the people who made the most progress were the collaborators and bridge builders, the includers and inviters, the broad-minded generalists and discipline blenders. The people who had the hardest time were the isolated excluders, the narrow-minded specialists, and the arrogant purists.” If you want to read more about that, download the free excerpt from Chapter 3 at my website.

You talk about “cultivating a specific perspective on failure.” How can we get organizations and individuals to be more comfortable with failure?

I think failure is hard for so many people because it seems final. But when we understand that failure is not the whole story nor the end of the story, when we see failure as a temporary step or as an unavoidable component of progress, when we see failure as the key to learning, it’s really much more palatable. Maybe even fun.

What industries or areas do you see failure being done “well”? And which ones not so well?

When someone dies, a bridge falls down, or an airplane crashes, those communities assemble a large group of doctors, civil engineers, or pilots to investigate what went wrong and prevent it from happening again. That’s one of the instances where studying failure can make a big difference. Medicine in particular does a pretty good job of learning and adapting when things don’t work. In contrast when a software development project goes pear-shaped or a technology development project doesn’t work out, we tend to bury that and act as if it never happened.

Dan, I enjoyed the book immensely. The history of the pursuit of flight was fascinating, your writing made me laugh out loud – always a good thing – and your lessons are useful and inspiring. What’s the best review you’ve gotten on this book so far?

I love that Andy Nulman said LIFT is “ebulliently written” (even though I always mispronounce the word ebullient). I can’t say I was deliberately aiming to write with ebullience, but when I saw that description I felt seen and knew I wanted to put that on the cover.

A few people have said the book sounds like me, it matches the way I am in real life. That makes me very happy, because that’s something I very much was aiming to do. I want my writing to sound genuine, which isn’t always easy, so that’s a really good review as far as I’m concerned.

Any negative reviews?

I haven’t seen any negative reviews yet, but I’m not too worried about those. A negative review basically means that I wrote a book, I finished it, got it published, I took a chance, I sent it out into the world, and someone read it. That feel a lot like success to me – the finishing, the completion. If someone doesn’t like it, well, that person probably wasn’t my audience in the first place.

Okay, we’ve talked about the book, so I’m sure listeners are wondering where they can purchase copies of LIFT?

Not at Amazon, and that’s on purpose. My first two books are available at Amazon, but with this one I’m deliberately aiming to go more local, more of an independent, small business approach. So you can get the paperback at Lulu.com, and the eBook is available at Barnes & Noble or Kobo. The audiobook is in the works, hope to have it done by the spring!