by jstarling | Feb 27, 2025 | Uncategorized

This post is by Elisa Miller and Mariam Ibrahim Chahine, ITK Facilitators at MITRE.

Organizational change is always a challenge because most teams perceive that change will be difficult, costly and weird. We were tasked with figuring out how to integrate a functional enterprise information technology (EIT) team into a larger acquisition team for one of our sponsors. The goal of the three-day workshop was to restructure EIT and the Acquisition teams into an efficient service-orientated team. During the workshop we realized organizational changes would be required to make this a success. The challenge of this workshop was to help the participants not only embrace change, more so to lead it and own it.

We led the teams through a series of exercises over the three days including:

- Challenge Discovery Exercises – to make sure all the participants were on the same page as to why they were there.

- Pre-mortem Exercise – to look at what the outcomes would be if this program was not successful.

- Eco-system Mapping Exercises – to identify strengths and uncover opportunities for growth within the organization.

- Defining the Customer Session – to discuss how the organization defines who their end customer is.

- Service Design Blueprinting Introduction and Initial discussion–to understand how these blueprints can be used to aid their upcoming ServiceNow implementation.

As facilitators we remained flexible during the workshops. Each afternoon, we met with the team’s leadership to discuss the next day’s activities. These discussions helped us reshape the next day’s plans and exercises to better meet the team’s goals.

The team expressed their enthusiasm about the potential benefits of service blueprinting; now they have a clearer and more structured understanding of their services and customers.

The plan going forward is for them to work on their organizational evolution and re-engage with the ITK team to create more Service Blueprints in preparation for their ServiceNow implementation.

by dbward | Oct 17, 2024 | Uncategorized

“…you look at a thing nine hundred and ninety-nine times, you are perfectly safe; if you look at it the thousandth time, you are in frightful danger of seeing it for the first time.”

― G.K. Chesterton, The Napoleon of Notting Hill

The Premortem tool is at the top of many people’s lists of Favorite ITK Tools. It’s certainly in my top 3, and I recommend it often!

I’ve done a few premortems lately and in the process I saw some room for improvement in the canvas itself. No, I haven’t done nine hundred and ninety-nine of them, but the opening quote from G.K. Chesterton came to mind as I realized I was sorta seeing this tool for the first time. I think the key was doing the several premortems back to back. That allowed me to see patterns I’d previously overlooked – repeated moments of confusion or gaps in the instructions.

So we’re going to update and refresh that tool a bit. We’re planning to add a “quality check” similar to what the Mission & Vision Canvases provide. We’re going to be a bit more specific in a few points, to provide clearer guidance on a couple steps. I’m excited to see what the refresh looks like and to share it with you all!

(PS – The Napoleon of Notting Hill is a terrific book, if you haven’t read Chesterton’s work you’re in for a real treat!)

by dbward | Aug 26, 2024 | Uncategorized

One of my favorite questions is “when was the last time you did something for the first time?”

For folks who are early in their career, the answer is often “this afternoon.” Life is full of first-time experiences when you’re starting out. But those of us who have been around a bit longer might find “first-time” experiences a bit harder to come by. It’s just math – but it’s also inertia and a tendency to stay in our comfort zones.

Last weekend, at the age of 51, I learned how to use a jackhammer for the first time as part of a Habitat for Humanity work session. That day was full of firsts, and was a nice reminder to myself of the importance of doing new things. Being a beginner does interesting things to our brains – we have to pay attention in a new way, we have to adopt an open posture as we try to figure out how to do this new thing. When I first squeezed the jackhammer handle I had no real idea how it would feel or how it would work. I really enjoyed being a rookie for a day.

Plenty of people stop trying new things, but nobody lives long enough to run out of new things to try. The world is full of opportunities to explore, experiment, try something new. The key is to look for them, to create them, and to accept them.

So… what is something new you might try?

by dbward | Aug 19, 2024 | Uncategorized

Collaborative culture building is the only kind of culture building. Nobody can build a culture on their own.

I find that explicit culture building efforts are relatively rare. In fact, one participant in a workshop I led defined culture as “that stuff we don’t talk about.” Another senior leader once told me “I don’t do culture, that’s too hard.”

There’s a lot of culture ignoring and culture avoiding instead of culture building. When we do talk about it, a lot of what happens is just culture describing rather than genuine building.

On a similar note, in a recent course on innovation and culture, the instructor insisted that “culture is invisible.” I really must disagree. Culture is very much visible… if we choose to look at it.

Every group has a culture of some kind, a set of “shared beliefs and behaviors” the group holds in common (that’s my favorite definition of culture). These cultural attributes are often unstated or implicitly accepted, without much deliberate discussion or decision. They often happen without people paying much attention to them. But the healthiest groups I’ve ever known are the ones where we do talk about it, where we do see it, where we do make choices about the beliefs we hold and the ways we express those beliefs. Where we go beyond just describing “how we do things around here” and get into “what do we think is really important?” and “how do we want to do things around here?”

We all play a role in building the culture of the groups we’re a part of, by the beliefs we hold and the behaviors we exhibit, whether we know it or not. Even if we’re not building culture deliberately, our beliefs and behaviors build culture every single day.

Here’s your invitation to play that role on purpose, to spark some conversations and build a culture you can be proud of.

by dbward | Aug 12, 2024 | Uncategorized

It’s not particularly helpful to advise people to “be a good communicator” or “do good work,” without giving some sense of HOW to do such things. Such advice is just a platitude that fails to produce action. When I come across that sort of thing in a blog or book, I tend to move on pretty quickly.

But in some cases, there’s an easy fix to that advice. Add the phrase “give yourself permission to…” at the front of the sentence. That often turns it into something much closer to a helpful insight.

“Give yourself permission to be a good communicator” could be helpful in an environment where death-by-PowerPoint is an acceptable standard for giving presentations, and where things like energy, enthusiasm, creativity, humor, personality, or other marks of effective communication are viewed with suspicion. This is particularly common in organizations that value technical aptitude over so-called “soft skills.” In organizations like that, people might even believe “you must not be very technical if you’re a good communicator.” In those cases, It could feel risky to give a good presentation, and so encouraging people to give themselves permission to develop and exhibit soft-skills.

Incidentally, soft skills are actually super hard, in every sense of that word.

by jstarling | Aug 5, 2024 | Uncategorized

This post is by Allison Khaw, an ITK Facilitator at MITRE.

The original Mission & Vision Canvas is a staple of the Innovation Toolkit—it addresses a common need, it’s impactful, and it’s fun.

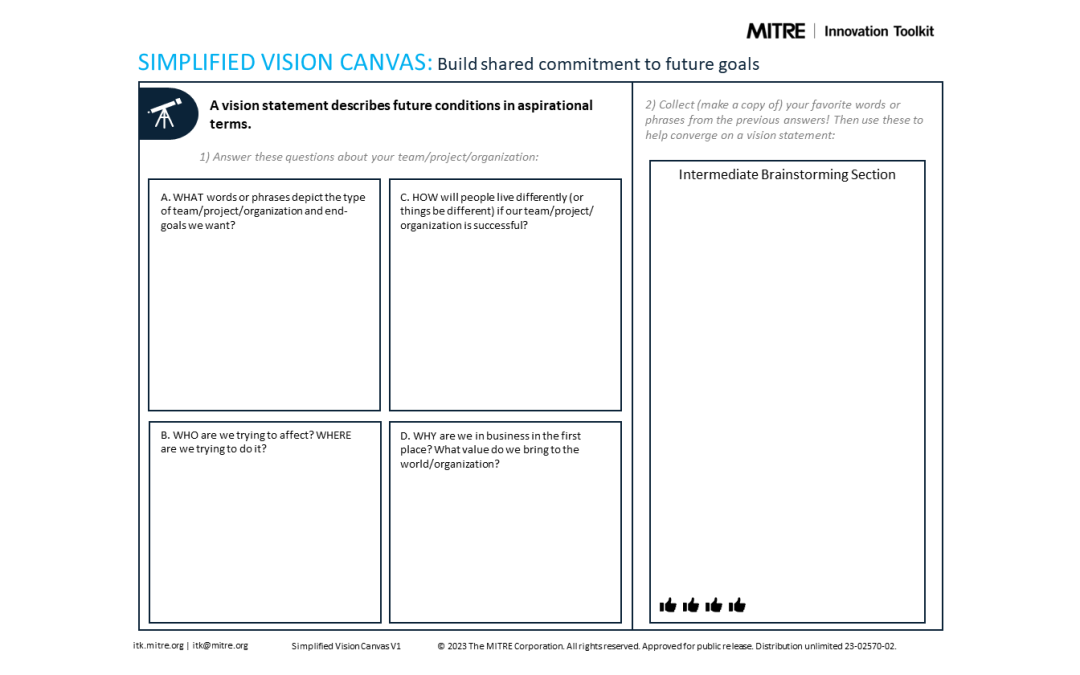

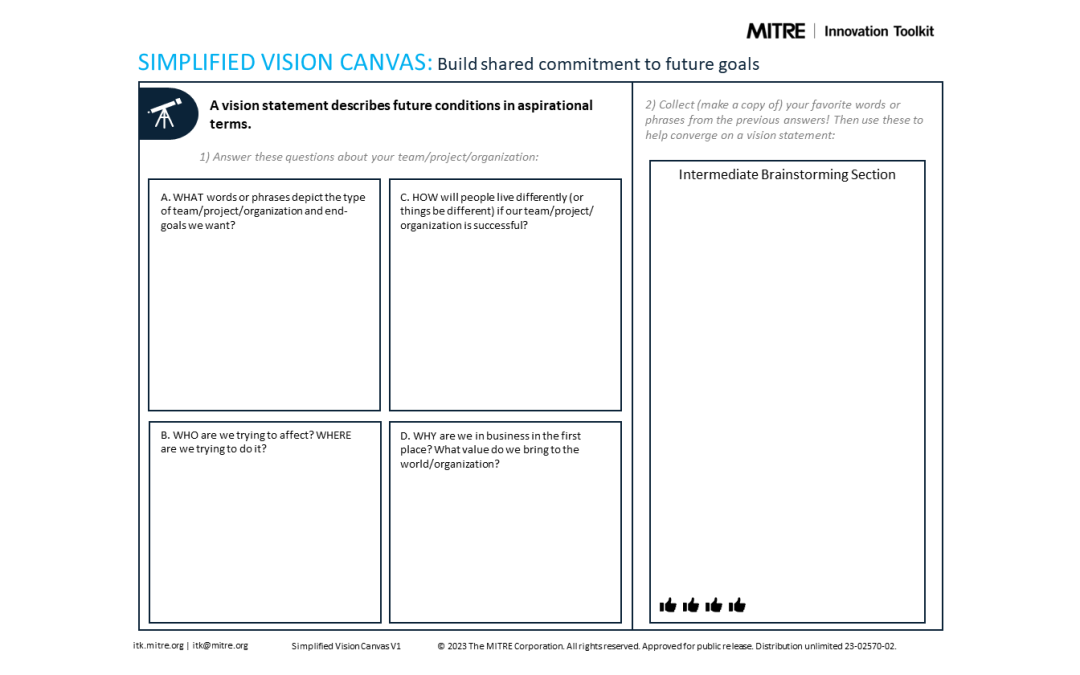

The Mission & Vision Canvas helps you develop new Mission and Vision statements or refine existing ones. A Mission is meant to be implementation-focused; it “describes present activities in concrete terms”. In contrast, a Vision is meant to be everlasting and inspiring; it “describes future conditions in aspirational terms”.

Even for tools that are well-established like this one, periodic revisions are usually worthwhile. Change is inevitable, after all, and evolving a product can have long-term benefits.

In early 2023, Gabby Raymond (another ITK Facilitator) and I discussed ways that the Mission & Vision Canvas could be improved, starting with the “Vision” half. We had used the tool a number of times, and we had ideas.

As we began experimenting, our ideas morphed into actual design changes. We wanted a clearer focus on “what”, “how”, “who”, “where”, and “why”; to do this, we redesigned the prompts to capture them as more informative questions. In order to reduce the barrier to entry, we added more helper resources, including a word bank and a variety of Vision templates. We also revisited the “Quality Check” and provided a fresh set of Mission and Vision examples from other companies. We even wanted a bigger intermediate brainstorming space!

All of this came from experience, but at the same time, it wasn’t obvious from day one—it took considerable time to articulate what we were looking for. Our intent was never to create a completely new tool, but rather to create an updated tool that highlighted the best parts of the original one while bringing forward complementary improvements to streamline the experience. With this in mind, we created the Simplified Vision Canvas.

How did we find our way to this updated tool? What follows is a set of six reflections on what worked best for us. Hopefully, this will prove valuable for your own projects!

1. Do your research. At the start, Gabby and I analyzed numerous Mission and Vision statements previously created using the Mission & Vision Canvas, as well as Mission and Vision examples from various companies. We looked for similarities in content and format, gauging ones that worked well and ones that didn’t. We also sought out general advice on developing Mission and Vision statements, eager to learn everything we could.

2. Build off of what already exists, rather than trying to create something from scratch. I want to emphasize again that we were intentional about keeping the foundational aspects of the Mission & Vision Canvas, because we knew it worked, and we didn’t want to lose that. Based on our practical experience, we focused on the parts of the tool that we believed should be modified. We simply wanted to make something already great even better.

3. Recognize that a low level of consistent progress is better than no progress at all. We worked on the Simplified Vision Canvas as a side project over seven months, assigning ourselves “homework” in between monthly meetings. Sometimes it’s easy to assume that a lack of substantial time to work on a task means you should wait to start. However, our incremental progress was key to finishing what we set out to do. We were “slow but steady”! (Just like the tortoise in the beloved fable… In fact, What if the Tortoise and the Hare Did a “Rose Bud Thorn”?) Looking back now, seven months was a more than reasonable amount of time to spend updating this tool. Discipline won over anything else here, and it was a lesson well learned.

4. Bring in test users to give feedback early and often. Once Gabby and I had created an initial version of the Simplified Vision Canvas, we held a test session with a small group of ITK team members and received valuable feedback. In hindsight, we probably could have held even more user sessions, earlier in the development process. Additionally, we focused most of our energy on updating the tool itself, but we could have benefited from doing targeted marketing to maximize the number of end users. A lesson learned for our next project? Absolutely. (Also, go use the tool!)

5. Develop your product/tool with a partner. Creating the Simplified Vision Canvas as a team of two, rather than a team of one, was markedly more effective—not to mention more fun. Our collaboration made us de facto accountability partners, and we benefited from diversity of thought. The end product would not have looked anything like it does today without our combined inputs. What’s more, working on a team allowed us to focus on the parts of the process that we were each most passionate about. Truly, it’s a win-win.

6. Adjust your expectations as you go, so that you can tie the bow on your product/tool and then dive into your next creative project. Gabby and I chose the “Vision” half of the original tool to update first, given that a high-level Vision statement is typically where a user would start. Although we aspired to update the “Mission” half of the tool next… we simply didn’t get to it. Oops! We may revisit this in the future, or we may not. Either way, I feel proud of what we did put together while also appreciating the potential for follow-on work.

Looking to try out the Simplified Vision Canvas yourself? There’s a free PDF version; a free and editable PowerPoint version (found on the bottom of the right side of the original Mission & Vision Canvas web page); and a reusable Mural template for MITRE users. Best of luck pursuing your very own Vision goals!