by dbward | Jun 28, 2024 | Uncategorized

The Irish poet & author John O’Donohue wrote a beautiful book titled To Bless The Space Between Us. One of my favorite bit in the book is titled A Friendship Blessing, which includes these words:

May you be blessed with good friends.

May you learn to be a good friend to yourself.

May you be able to journey to that place in your soul where there is great love, warmth, feeling, and forgiveness.

May this change you.

That last line really hits me – the way friendships change us in positive ways. I’ve been co-teaching a series of courses lately (with the friend who gave me O’Donohue’s book!) and it’s got me thinking a lot about the concept of change and how that is one of the main goals of education & training. As we introduce new concepts and lead exercises, in the back of my mind I find myself thinking “may this change you” (and reflecting on the ways it’s changed me!).

If the classes and conversations don’t change us, then they’re just an amusement. I like amusements, but we are aiming for something more significant than that. We’re looking to make some change. And by “change” I don’t mean picking up a new technique or applying a new tool. I’m talking about something more foundational. ITK training aims to move us all towards a more open, iterative, experimental, collaborative, playful, curious way of working. It aims to move people away from an individualistic, perfectionist, control-oriented pursuit of certainty, predictability, and power.

That kind of change doesn’t happen overnight. It doesn’t happen in a classroom. It takes time and deliberate effort to establish and sustain this way of working out in the world. And it also DOES happen in a moment, when we decide to go in this direction. Or maybe it happens in a hundred moments, as we keep deciding and taking action.

I hope this ITK project sparks real change in all the people we touch. I hope it brings the blessing of good friends doing good work together, in ways that changes us and the world around us.

by dbward | Oct 2, 2023 | Facilitation Tips

Today’s blog post is by Starling Jaquan (with some help from Liz Roberts), two of ITK’s newest certified facilitators!

In today’s world where remote collaboration has become the norm, facilitating a large group presents its own unique set on challenges. In this context we are defining a large group as a group of 20+ people. In this post we will explore best practices for facilitating large online meetings, drawing upon past experiences and proven techniques to help you navigate this complex terrain.

The Challenge of Large Meetings

Before diving into best practices let’s explore why facilitating large meetings can be particularly challenging in the online realm.

- Simultaneous Voices. In a large meeting multiple participants may chime in at the same time which can lead to confusion among meeting attendees.

- Increased Opportunity for Disagreement. As the group size grows, so does the potential for differing opinions to come to light. These disagreements offer the opportunity to resolve conflict and come to shared understanding.

- Uneven Participation. In a remote meeting, not all participants may actively engage or vocalize their thoughts, leading to valuable input being missed and not contributed.

Before the Meeting

Consider using breakout rooms Breakout rooms offer the opportunity for more intimate discussion where team members may feel more comfortable sharing their thoughts and ideas. In this smaller setting, the dynamics change, and voices that might have stayed silent in a larger group may start to chime in.

Have a Co-Facilitator (or multiple!) Having a co-facilitator (or multiple) by your side is like having a trusted companion on an epic journey. Your co-facilitator(s) can help share the workload and responsibilities of navigating the vast landscape of a large group. Before you and your co-facilitator go into the meeting discuss what roles you might take – one person can monitor the virtual board while the other keeps an eye on the chat.

Understand Technology Limitations Some participants may not be familiar with the technology (Mural, for example), or may not be able to access certain online tools. Or maybe the information is too sensitive to be posted in certain channels. As the facilitator, you’ll need to be prepared to explain the landscape and ensure everyone is up to speed.

During the Meeting

Embrace the Silence In the midst of a virtual meeting, silence can be a powerful ally. Instead of fearing it, embrace it. Allow for moments of quiet reflection. These moments give participants the space to think, to digest, and ultimately to speak up.

Monitor the Chat If you are using a system that provides chat capability as well as audio & video, think of the chat as a parallel dimension where voices are typed rather than spoken. In large groups time is precious and not everyone may have the chance to unmute their microphone. This is where chat comes to the rescue. Having a facilitator dedicated to monitoring the chat ensures that no ideas go unnoticed.

Encourage Use of Cameras In the virtual realm cameras can be your window into participants thoughts and emotions. Encourage those who are comfortable to turn on their cameras. It’s like flipping the lights on in a dark room – suddenly you can see the expressions, reactions, and connections that were previously hidden.

Acknowledge Contributions In a sea of voices finding common ground can be like discovering treasure. Encourage team members to acknowledge ideas they resonate with. This helps team members feel that their input is being valued fostering a sense of camaraderie and collaboration.

After the Meeting

Asynchronous Input If you’re using a virtual whiteboard (like Mural), keep it open for additional input even after the meeting, allowing those who were not present during the meeting to contribute. This also allows for people to add in ideas that pop into their head after the workshop.

In conclusion, successfully facilitating a large online meeting is similar to embarking on an epic journey. With careful planning, effective use of technology, and a commitment to inclusivity, you can navigate the challenges and turn these gatherings into opportunities s for innovation and success.

by dbward | Sep 11, 2023 | Uncategorized

This week’s blog post is by Starling Jaquan. Illustration by Francis Cleetus

You are starting off on a new project with your team. The air is filled with excitement and anticipation. Each member brings a unique set of skills and perspectives to the table, so you might wonder how to foster team morale, ensure everyone is on the same page, and build a shared understanding that fuels our collective success?

A team collaboration plan is a powerful tool to pave the way for effective collaboration. It outlines the strategies for working together to achieve your collective goals.

Without a well-defined structure even the most talented teams can struggle to align their efforts. A team collaboration plan is a roadmap that guides your team to a shared destination. Each member’s aspirations and expertise are acknowledged, so everyone’s contributions are valued. Collaboration is a delicate dance, and sometimes disagreements emerge. Conflict is inevitable, and a collaboration plan establishes a process for approaching conflict constructively.

How to Approach Creating a Team Collaboration Plan

The whole team should be in the room when creating the plan, so that everyone’s input is heard and included. Making a team collaboration plan is not just about drafting a document, it’s about fostering a sense of ownership among team members. At every step along the way allow for team members to vocalize their thoughts on the following topics.

1: Team Goals

What do you aim to achieve as a team? In this crucial step collectively define your team’s overarching objectives. Be specific and make sure that everyone is on the same page.

2: Individual Goals

How does everyone envision growing, learning, and contributing? Allow each team member to express their personal goals for the project. This step promotes transparency and helps align individual aspirations with the team’s mission.

3: Success

What does success look like for everyone involved? Collectively envision what achievement looks like for your project. Allow everyone to think about this holistically and consider what success looks like as both a team and individually.

4: Communication Channels

When might it be more appropriate to send a message over Microsoft teams versus an email? Discuss and decide how the team will communicate. Define preferred communication channels, expected response times, and related responsibilities.

5: Conflict Resolution

What does a successful conflict resolution look like? Anticipate conflicts and outline a strategy for resolving them. Establish a process for addressing disagreements and ensure that everyone is commitment to respectful communication, even in challenging situations.

6: Accountability Mechanisms

How will the team track progress to ensure that tasks are completed and that deadlines are met? Discuss how the team might develop a system for holding each other accountable. Accountability keeps the team on track and motivated.

7: Formalize the Collaboration Plan

Draft the plan and send it to the team for review. Make sure the plan includes everything the team discussed and agreed on. Encourage open feedback and adjustments as needed. Once everyone is on board, make sure the final version is accessible for all team members.

A team collaboration plan is a living document, as the project evolves revisit and revise the collaboration plan periodically. Remember, a collaboration plan is designed to empower not constrain. The plan is a tool to guide the team, not a rigid set of rules.

The next time you have a team that is starting on a new project consider creating a team collaboration plan. A team collaboration plan acts a roadmap to ensure everyone is headed in the same direction while fostering a positive and productive team environment.

by dbward | Aug 21, 2023 | Uncategorized

Today’s blog post is by Liz Roberts. Image courtesy of Palle1958 on Pixabay

I am always amazed when I see beautiful flowers grow in unexpected places, such as a city sidewalk. How is it getting enough sunlight? How has no one stepped on it? How did the seed get here? I recently had several experiences that reminded of these amazing flowers as I witnessed surprising ideas bloom during Lotus Blossom experiences.

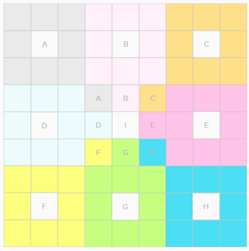

Lotus Blossom – each colored 3×3 square is a blossom with a theme in the middle, each individual square in a petal storing an idea.

What is the Lotus Blossom Exercise?

The Lotus Blossom is an exercise that encourages idea creation. The structure consists of a standard combination of eight blossoms, or themes, where each blossom has eight petals or ideas. Although it is usually done in a group, it can also be just as effective when done individually. There is also no strict limit to the number of ideas generated and you should feel comfortable expanding beyond the original design. Because I am a Sudoku fanatic, the layout of the Lotus Blossom board always reminded me of the 9 x 9 zone-within-a-zone design in a Sudoku puzzle.

So back to the flower.

New Flowers in a Familiar Field

There I was, facilitating a Lotus Blossom exercise to help colleagues become familiar with the core competences needed for a leadership position. I used the leadership competencies, which I have become comfortable with over the past years, as the blossoms. I did the exercise with two distinct groups of participants, and I went into the activity expecting to see familiar ideas. I was blown away by the number of new, fresh ideas that I saw on the blossom petals. In some cases, I saw the competencies in new ways. I also realized that some impressive ideas did not fit into any competency but were amazing and should be demonstrated by leaders. I saw new flowers blossom in a field that I thought I knew so well.

New Flowers Spread Seeds

A few weeks later, I decided to use the Lotus Blossom again for a different event focused on brainstorming ideas on learning and career growth. I prepopulated the themes based on eight broad categories for how MITRE colleagues typically learn and grow. As the participants were adding ideas, I noticed one of the blossoms getting full, so I mentioned that they can add more petals in the white space right beyond the original eight petals. They surpassed the original goal of eight ideas by five additional new ideas! Here is what surprised me though – it was for on-the-job training. I wrongly assumed that blossom would have the fewest ideas. During our discussion, we all agreed that this was very exciting since on-the-job is where our staff spend most of their time. It was encouraging to see so many creative ways to take advantage of this training opportunity. We ended up with an actionable list to share with our staff on ways they can immediately start infusing training into their day-to-day job. This blossom might result in our staff blossoming in their own careers.

Encouraging New Ideas

During the Lotus Blossom exercise, here are some phrases you might try to nurture innovative ideas:

- “If you think it, ink it” to encourage people to capture their own ides in their own words.

- “Who have we not heard from?” to encourage quieter participants to join the conversation and share their ideas and can serve as a gentle signal to dominant voices to step back for a moment and make room for others.

- “Yes, and…” to enable candidness, which unlocks openings for key insights. The phase also enables creativity, which widens the aperture for what is possible and expands thinking in new ways previously blocked. To learn more about this powerful phrase, read the ITK Blog on What is ‘Yes, And…’?! and 7 Tips to Practice ‘Yes, And…’ During Everyday Collaboration.

If you have not tried a Lotus Blossom exercise, I recommend looking into it and seeing how you can help new ideas bloom for you and your teams.

by dbward | May 1, 2023 | Misc Awesomeness |

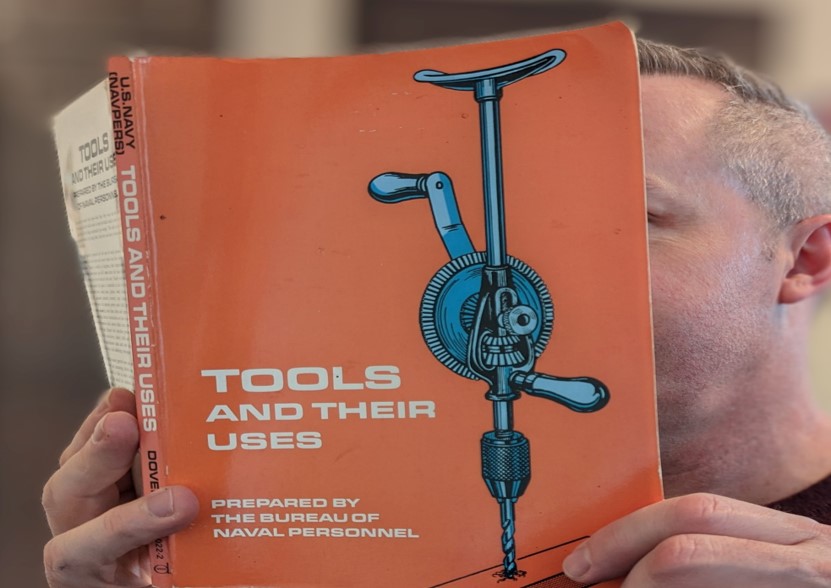

When we first created ITK, there’s a reason we adopted a tool metaphor. We wanted to amplify the concept that tools are used to make things. Sure, it can be fun to become an expert in a particular tool (or toolkit!), but what matters most is not the tool itself. What matters is the thing you make.

The tool metaphor also highlights the fact that tools can be used in lots of different ways. A claw hammer can be used to sink a nail into a piece of wood. It can also be used to pull the nail out. I bought a screwdriver so that I could drive screws. But do you know what I mostly use that tool for? Prying open paint cans. And don’t get me started on my power drill (which I mostly use to drive screws, not to drill holes).

In keeping with this metaphor, we encourage creative use of the ITK tools. You are free to use these tools far beyond the typical applications and standard procedures. Avoid the purist approach, as if there is only One Correct Way to use the ITK tools.

By all means, use your hammer to sink a nail. Just keep in mind that it can also do the opposite.