by dbward | Jul 15, 2019 | Uncategorized

Today’s post is the first in a series by guest bloggers Alex Feinman (with Tom Seibert and Tammy Freeman)

Sometimes, you have to mix and match methods to get the results you need. This story is example of how important it is to be able to modify and adapt the plan in response to new facts and constraints.

MITRE was called in to facilitate a conversation about replacing or upgrading a COTS piece of software that a sponsor was using. We put together a session that began with knowledge elicitation, to understand their domain; then focused on establishing user requirements; finally some progress toward conclusions and agreements on actions.

The sponsor sent close to 30 people to the two-day event. MITRE brought in a team of facilitators to help manage the large number of people.

While our team had some experience with the software in question, we also had more experience with other, better software. Hence, we were expecting to elicit the sponsor’s needs, as a step toward potentially guiding them toward a better option.

This plan, as they say, did not survive contact with reality.

The Map is Not the Terrain

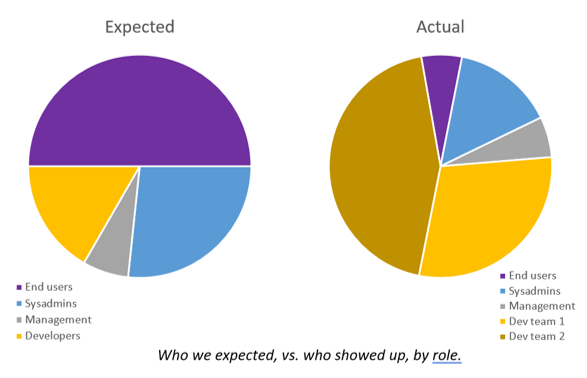

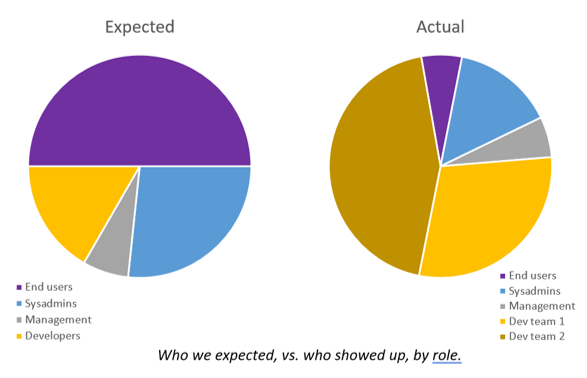

We were expecting our participants to be a mix of end users, ops/sysadmin folks, and program administrators. Instead, on arrival, we discovered that the bulk of attendees were developers—some sponsor-based, and some who were contractors.

The two sets of developer were working on competing systems, both used by the sponsor. End users had to switch between these systems to get their work done. In addition to this, we had only a few actual end users, plus a number of sysadmins, who sat between those two populations.

The group was on the edge of fracturing, with finger-pointing starting to become more apparent—the makers of each system were defending their turf and jobs, and beginning to think about bad-mouthing the other “team”. It was time to help these developers understand how things looked from the user’s perspective, and fast.

Day One: Finding Common Ground

After a quick consult, the facilitators decided to continue to gather data on the work context—getting a sense for what things were on everyone’s minds about the systems. Concerns by most users centered around ease of use issues, responsiveness (or lack thereof) from development teams, and annoyances related to switching between two different systems with similar purposes. Concerns from sysadmins and developers centered on deployment and provisioning, and licensing of third-party data sources.

We used dot voting to identify which concerns were foremost. This backfired slightly: nearly everyone voted for “merge the two systems”—a solution masquerading as a pain. Additionally, some near-duplicates needed to be merged. In retrospect, we could have used a round of affinitization or Stormdrainingto reduce the number of issues prior to voting.

Based on this finding, we decided to dive into understanding why the systems were currently separate, and whether there were any benefits there. A subgroup worked to put together a rough system diagram on a whiteboard wall. This revealed a huge amount of complexity hiding behind the user interface and helped legitimize the current split situation. One of the systems had strong processing capabilities, while the other had a much stronger UI. With this brought to light, we worked to help the group see that there might be a double-win involving pieces from both systems.

Armed with this data, we gave the group six areas to focus on, ranging from user workflows and UI issues to system administration, data ingestion, and data processing. This allowed the group to break up naturally by role, which was both helpful and harmful—helpful in that each group made progress, but harmful in that it did not work toward building group coherence. However, it was a necessary step toward group formation—letting the folks there understand that we were intending to listen to them, understand their situation, and help them prioritize their concerns.

Informal discussions, such as those happening over lunch, were critical to getting folks to buy into MITRE’s role as an unbiased facilitator. These conversations helped cement their trust that we weren’t there to put half of them out of work, weren’t there to promote one system over another, and certainly weren’t there to sell them on software we created.

We also invested time with particularly reticent folks to bring them around to seeing other people’s perspectives, and give them hope of open lines of communications. While often overlooked during use of ITK “methods”, these informal conversations can make or break a long event such as this one!

By day’s end, we had a commitment from everyone to keep working together and keep talking—a great start given where we’d begun.

Stay tuned for the rest of the story in next week’s episode!

by dbward | Jul 8, 2019 | shared leadership, Team Toolkit

Knights of The Round Table

I often say the best thing Team Toolkit ever built was… the team itself.

Team Toolkit operates with a collaborative structure where each member has a lot of room to use their strengths, to support each other, and to have fun doing it. It’s a very low-ego environment, where we know each other’s strengths and celebrate each other’s contributions.

The team has terrific chemistry – we genuinely like each other. On the one hand it’s not possible to force this or manufacture good personal chemistry, but on the other hand this sort of thing does not happen by accident. Positive relationships within a team require a mix of deliberate effort and good luck.

From the start, Team Toolkit made it a priority to build these friendships and foster a certain type of environment. The fact that we worked on it and did it on purpose doesn’t make our relationships less real. It makes them more real.

Our mutual respect and appreciation for each other also made it easier for us to adopt a collegial, shared leadership structure, where everyone is able to make decisions and guide the direction of the team. There is no a single formal leader with executive decision-making authority for the team. Instead, everyone has the same authority. You could say it’s a leaderless group, but it is definitely not a leadershipless group. There’s a ton of leadership on Team Toolkit, and it comes from all of us.

For example, when someone has an idea for a new tool, workshop, or activity, we present the idea to the group and see who might be interested in doing it. We’re not assigning tasks or asking for permission as we would in a top-down style organization. Instead, we’re informing and making invitations. There is someone who leads each activity, and it varies depending on people’s interests, skills, and availability. In keeping with that spirit, let’s hear from some other members of Team Toolkit:

“The Shared Leadership structure shows up in our team meetings when no one person runs it every week. We take turns. Everyone runs point on workshops/has connections that they bring to the table.” – Rachel

“We play to each other’s strengths, both in sessions and through our weekly meetings. We acknowledge that we aren’t all experts, and are constant learners – learning from each other and from our shared experiences.” – Melanie

“The diversity of our team’s strengths and interests helps to ensure that folks commit to leading initiatives that they are genuinely interested in or good at, which leads to better results. i think we have strong trust too that you don’t have to worry about what’s NOT on your plate. You know other team members will deliver and that someone on the team will have your back/help if you should need it.” – Aileen

It’s a tremendously efficient and effective approach, and I think more groups should adopt it. There’s a lot of great research & resources out there about shared leadership, so if you want to learn more, consider starting with this piece by Joanne Fritz.

by dbward | Jul 1, 2019 | Tools 101 |

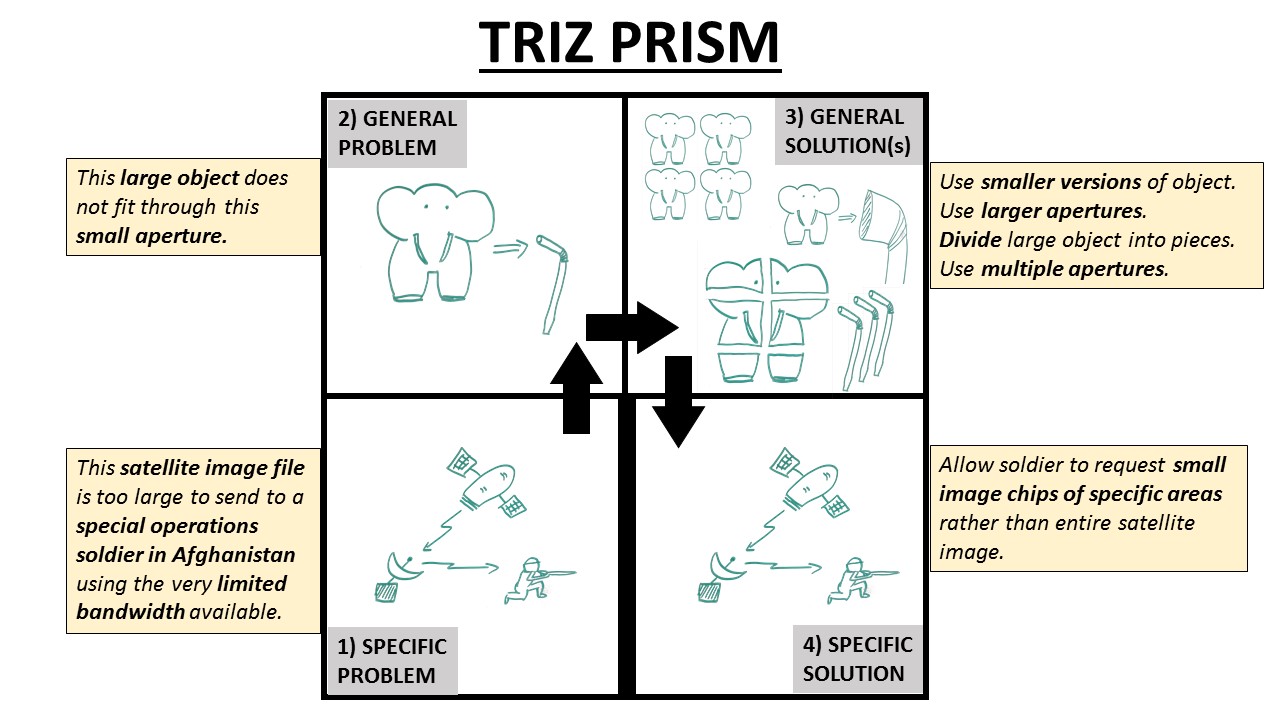

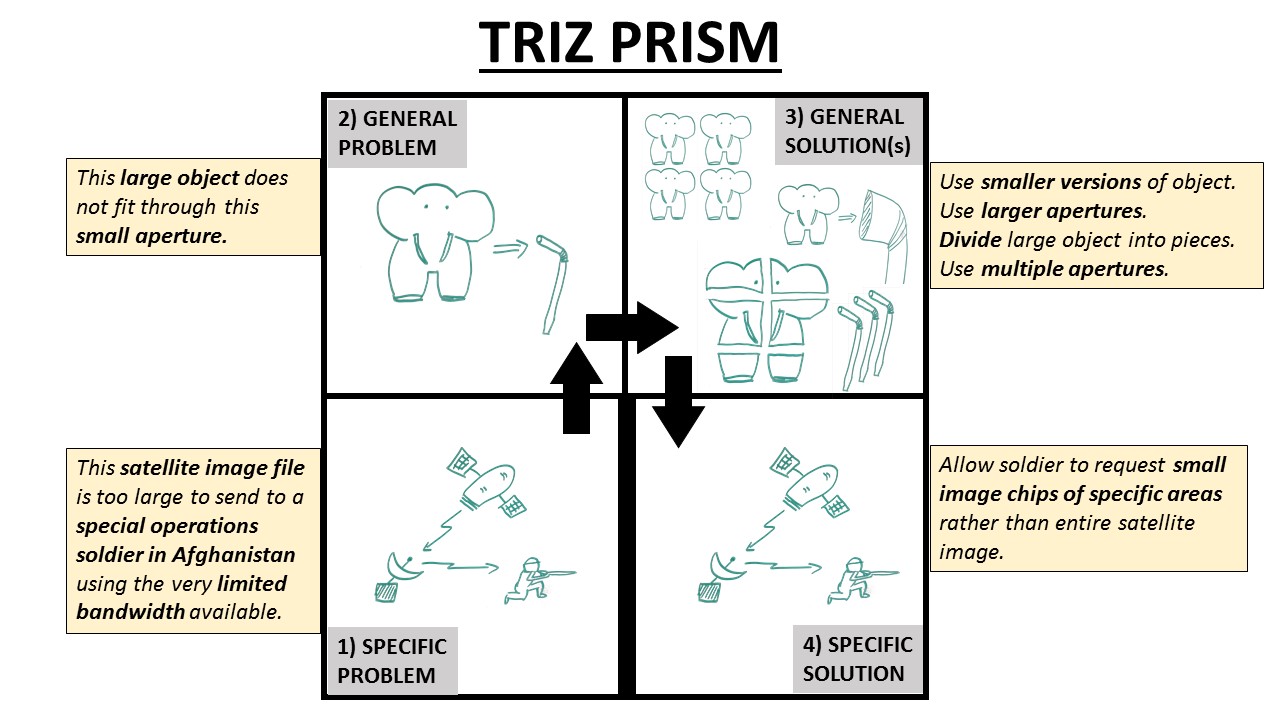

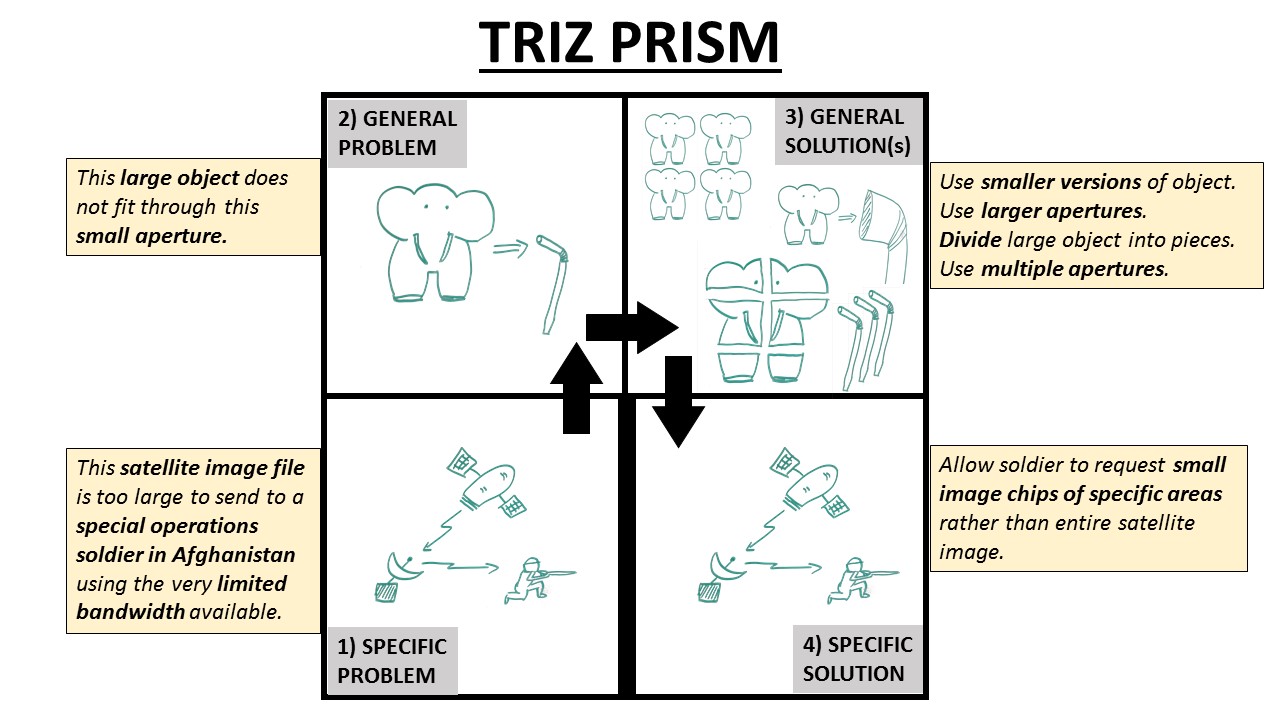

The TRIZ Prism tool is a powerful way to unlock a team’s creativity and discover new solutions to difficult problems. It’s a pretty straightforward practice to describe, but actually doing it can be a little trickier than it looks at first.

The Elephant-And-Straw example in the image below is based on a real-world project Dan worked on. The activity begins in the lower left corner (the box labeled 1 – Specific Problem), we wrote a very specific problem description… and realized it was a really hard problem, with no clear solution.

That’s where the TRIZ Prism comes in. We then stripped out all the particulars and developed a general problem statement. We came up with “the big thing does not fit through the small aperture,” then explored general solutions to that category of problem. Once we came up with some general “types-of-solutions-to-that-type-of-problem,” we reintroduced some specifics and came up with a specific solution. That may sound like an obvious way to generalize & summarize the problem, but getting there took significant effort.

How did we do it? In a word – incrementally. The process of moving from Box 1 to Box 2 went something like this:

- How can we get this satellite image through this bandwidth to this soldier on this timeline?

- How can we get anything through this bandwidth to this soldier on this timeline?

- How can we get anything through any medium to this soldier on this timeline?

- How can we get anything through any medium to anyone on this timeline?

- How can we bet anything through any medium to anyone on any timeline?

- How can we get anything to anyone?

With each version, we removed one level of specificity and replaced it with a generalized version. Alert readers may note that #6 does not say “How can we get a big thing through a small aperture?” That’s because #6 in the list above is actually not a very good generalized statement of our problem. We needed to massage it a bit and re-introduce some specifics to get something truly useful for our situation. I mention it to highlight the fact that any specific problem can be generalized in multiple ways… and some are better than others.

From “how can we get anything to anyone,” we put some of the specific constraints back into the problem statement and went with “How can we get a big thing through a small thing?” That statement has enough specificity to be useful, and is general enough to be open to a wide range of solutions.

We then explored a wide range of typical solutions to that category of problem, and came up with a specific solution that allowed the soldiers to draw a simple polygon on a map and request a small image chip. It worked great.

Interestingly, that solution meant our initial problem statement was actually a bit off base. They didn’t need the whole elephant in the first place. They just needed the trunk. And it turns out the trunk fit through the aperture nicely.

Disclaimer: No elephants were harmed in the production of this example.

by dbward | Jun 24, 2019 | Tools 101

SCENARIO: It’s Friday morning. You’re an analyst and just received an urgent request for an analysis due Monday. You are 99% sure a colleague has done this same analysis before, but you have no idea where it was stored. Your options are 1) spend all weekend searching for that old analysis and updating it, or 2) start from scratch and finish a new version by the end of today. Which option do you choose? Is it more efficient to reinvent the wheel? Or to spend the time looking for something which may not be found – or may not even exist?

It often feels like we are stuck choosing the lesser of two evils when faced with a decision like this. Option 1 is risky – what if you don’t end up finding what you need, and you wasted all that time searching? Option 2 can be frustrating – you are pretty sure someone else has done the work already, but you simply don’t have time to figure out how to leverage it.

Team Toolkit recently delivered a workshop to help a group of intelligence analyst to explore solutions to that scenario. We began with a tool called the “Problem Framing Canvas”, which aims to help build a consensus about a problem statement and make sure the team is solving the right problem to begin with. After some discussion, the group agreed that “analysis takes too long” was a pretty good description of the problem. It’s short, clear, and does not dictate a specific solution.

It can be tempting to skip the “defining the problem” phase and move right into “solving the problem,” but building a consensus about the problem is always a worthwhile exercise. The Problem Framing Canvas helped the group identify other groups who also experience this problem (spoiler: MANY other teams) and who has figured out how to solve this problem (not many have – it’s a hard problem!).

After framing the problem, we moved to a second tool, Journey Mapping. A Journey Map is a visual tool that focuses on a user’s experience. It identifies phases, steps, actions, opportunities, and pain points in the analysis process, starting with the request for a product and ending with delivering the product. The process of developing such a map is often just as valuable for the team as the product itself.

Because the participants were geographically dispersed across three different locations, we paused our Skype call to allow each location to sketch out the journey of a typical analyst on the whiteboard, including steps that are typically challenging to accomplish. We then regrouped to share ideas and consolidate everyone’s work into one giant journey map.

The Journey Map highlighted points within the process that contribute to the problem and make analysis take so long. It also helped the team identify opportunities to introduce new processes, practices, and technologies that could speed things up. Participants left the workshop with a visual map of their process and a consolidated list of requirements for a new platform solution they could build, to help analysis go faster.

Hat Tip to Andrea & Allison for co-authoring this story

by dbward | Jun 10, 2019 | Uncategorized

Blackout poem by Austin Kleon (austinkleon.com/)

The first time you swing a hammer, you’re going to bend some nails and probably hit your thumb once or twice. Even though a hammer is an exquisitely simple tool, getting good at using a hammer requires practice (and if you’ve ever seen a master carpenter use a hammer, it’s a thing of beauty – google “Larry Haun human nail gun” if you want to explore that particular rabbit trail).

The same is true with the techniques and methods in the Innovation Toolkit. Each one is delightfully low-tech and deliberately simple… but don’t be surprised if the first time you use one, it’s harder than it looks.

I encountered this situation first-hand when I introduced the Lotus Blossom to some high school interns. This is probably the simplest tool in the whole kit, and although they understood the application right away, they struggled mightily to figure out how to use it. I let them wrestle and flail for a while, exploring and experimenting with how to use the Lotus Blossom on their project. Then I showed them how I would have done it – in less than five minutes, we had a clear, useful artifact they could use for the rest of the project.

The point is, when it comes to tools, mastery takes time and practice. Be patient with yourself. Don’t get discouraged if you bend some metaphorical nails. Find a coach who can help guide you through the process. And most of all, don’t give up.