by dbward | Jul 17, 2020 | Uncategorized

We all used to have in-person meetings for collaboration and ideation activities. Then COVID-19 hit. And quarantine. And we all scrambled to maintain collaborations across stakeholders despite the inability to continue in the usual ways. And as you no doubt have noticed, there are critical differences between planning and executing a successful virtual collaboration and the traditional in-person events. It’s not as easy as just doing the same old stuff, but this time on video. We have to make a whole bunch of other changes, and they aren’t easy or obvious. That’s precisely where we’d like to help.

We all used to have in-person meetings for collaboration and ideation activities. Then COVID-19 hit. And quarantine. And we all scrambled to maintain collaborations across stakeholders despite the inability to continue in the usual ways. And as you no doubt have noticed, there are critical differences between planning and executing a successful virtual collaboration and the traditional in-person events. It’s not as easy as just doing the same old stuff, but this time on video. We have to make a whole bunch of other changes, and they aren’t easy or obvious. That’s precisely where we’d like to help.

For a little background, check out Virtual Experimental Conference Delivers Real-World Results. That article basically describes an experiment we did, where a “coalition of the willing” from across MITRE’s Acquisition Disruptors (aka, the MAD Team) and the MITRE Innovation Toolkit (ITK) came together to respond to the unfortunate cancellations of the innovation collaboration events, pivoting from physical events into on-line events. We have planned and executed several events since that fateful day.

As we began reflecting on the experiences over the past few months, we took time to examine the virtual collaboration problem, which resulted in the following problem statement:

How might we create ways to continue collaborating with our Sponsors across multiple levels of classification while considering restrictions on physical proximity and the lack of accepted virtual environment norms/protocols as we aim to effectively solve problems to create a safer world?

With the help of MITRE’s Kaylee White as our lead facilitator, we ideated (ie, brainstormed) the key attributes associated with the virtual collaboration problem statement using our personal experiences and the Lotus Blossom tool from ITK. When Kaylee showed us the final product, we realized, “Hey! This is the beginning of a checklist to enable effective planning and executing of virtual collaboration events!”

And so, the “It’s Not a Checklist” Checklist was born. While it is far from a complete set of activities and considerations needed to deliver a successful virtual collaboration, it’s a pretty good starting point. We have shared the information with MITRE teammates, and received very positive feedback. So, we would like to take the sharing a step further and offer the information here for your use. The presentation is approved for release – so feel free to share away!

Are you using the Not a Checklist? Did it help? Did we miss any key items? We welcome your feedback! Please share your experiences and ideas. Thank you!

by dbward | Jul 6, 2020 | Tutorials

NOTE: This post originally appeared as a LinkedIn article.

These days we’re all increasingly aware of significant problems that need to be addressed, whether it’s the pandemic or systematic racism or climate change. Naturally, we’d all like to do our part and lend a hand, but it’s not always clear how to start. Here are five questions you may want to ask as you look for ways to be helpful and make a difference.

1) What is already being done in this area?

Before launching a new effort, take some time to educate yourself about what activities are already under way. Get to know the organizations and people working in that space, understand their efforts, priorities, and activities. This way you avoid reinventing the wheel, operating at cross purposes with like-minded people, or inadvertently undermining work that others are doing. Plus, if someone else is making progress, you may be able to work together and make a difference sooner than if you were starting from scratch.

For example, several of my colleagues and I were planning to attend South By Southwest this year. When the conference got cancelled because of the pandemic, the first thing we did was look for something to do instead. Specifically, we asked the question “Is anyone putting together a list of online talks and workshops, or maybe some local in-person events, now that nobody is going to SXSW?” We hoped the answer would be yes, but after several days of research and outreach, we were unable to find any such effort, so we started to think about doing something ourselves. This led to the next question.

2) Would it be helpful if we did __________?

If you’ve got an idea for something you think would be helpful, it’s wise to check with the people around you to see if they also think it would be helpful. A posture of curiosity, humility, and generosity will go a long way in building a coalition to actually do the thing, as well as ensuring that good intentions produce good results. Framing the idea in the form of a specific question – and being open to a variety of answers – is a much more inclusive message than simply saying “I’m going to do this.”

To continue the example, our specific question was along the lines of “Would it be helpful if we posted a lightly curated list of links to online talks about innovation and creativity?” We weren’t committing to doing anything just yet, and we weren’t suggesting we could recreate the whole conference experience (or even a meaningful slice of the experience). In fact, it wasn’t even about SXSW anymore. Instead, we described a modest idea that we thought might bring people together to share some ideas, and asked if that sounded helpful.

The response was overwhelmingly positive. More than 70 people immediately responded to say they would find such a list helpful. Even better, a bunch of them offered their assistance (jumping ahead to question #3). Of course, you can’t please everyone and the answer wasn’t unanimous. One person objected that this list would be unhelpful. We tried to be respectful of that position, accommodate their concerns, and cause no harm, while still honoring the larger group’s interest. That led to the third question.

3) Who wants to do this with us?

After learning about current efforts and soliciting feedback about your proposed idea, the next step is to see whether anyone wants to do it with you. If the second question is about interest, this one is about commitment and collaboration.

As our “list of talks” idea continued to mature, we made a wide-open invitation to anyone who wanted to join in. Loads of amazing people offered to provide amazing content. The benefits of collaborating are obvious and we don’t need to belabor that point. But the really cool thing about this question is it may help you discover potential partners you did not find after asking question #1.

That was certainly the case with us this past March. While our initial research did not uncover any organized effort to assemble a list of innovation-related webinars and presentations, it turns out we were just a little ahead of the curve. A few other groups began developing a similar idea right around that time, and this third question helped us find them.

Specifically, the Defense Innovation Network Summit (DINS) and the Public Spend Forum (PSF) both hosted online sessions that coincided with ours. They were excited to partner with us, so we added their links to our rapidly growing list and a few of us even gave presentations on their platforms.

Two weeks after asking our first question, we kicked off Innovation Resiliency 2020. This was a full day of online presentations, panels, book talks, and discussions, on topics ranging from improv to aviation to learning from failure. Our final list of talks included 16 presentations, plus 15 presentations curated by DINS (with even more on other days), and a big list of PSF’s events across that whole week. We could not have done any of it without the generous, enthusiastic, creative partners who came alongside.

4) What did we learn so far?

If the first three questions are focused on being helpful now, this fourth question increases the odds we’ll be helpful in the future. Solving problems is an iterative process, and every finish line is actually the starting line for your next race. So be sure to do a little reflection along the way, putting in the effort to collect lessons and insights for the future.

The full list of things we learned from the Innovation Resiliency project goes well beyond the scope of this article, but trust me, we learned a ton and have applied those lessons to several other areas.

One thing to keep in mind when asking this question: you don’t have to wait until you’ve done the thing. In fact, even though it comes fourth, this is a pretty good question to ask at every point in the process.

5) What might we do next?

This capstone question wraps up the results of the first four. How we choose to answer it will depend in large part on what’s been done so far and what help is still needed. It will depend on who’s involved and what we’ve learned. Answer the first four questions well and this fifth one should practically answer itself.

And of course, one of the things you might do next is… tell your story and share your lessons, just like we did with this post.

by dbward | Jun 1, 2020 | Interviews

We recently sat down for a video chat with Michelle Histand, Director of Innovation at Independence Blue Cross. It was a lively discussion about her work at Blue Shield and the innovation toolkit she uses, enjoy this 11-minute video! Don’t miss the Assumption Busting tool she describes at 6:30, it’s terrific!

by dbward | May 11, 2020 | Tools 101

The newest tool in our Innovation Toolkit is the Mission & Vision Statement Canvas. This is a great tool to use when forming a new organization, or any time you need to clarify a group’s activities and purpose.

To get started, gather your team and spend a few minutes discussing the objective of the session and the difference between a Mission Statement and a Vision Statement. These terms are often used without being defined, so a brief explanation up front can help get everyone on the same page and reduce confusion. We suggest that a good VISION statement describes future conditions in aspirational terms. In contrast, a good MISSION statement describes present activities in concrete terms.

One of our favorite examples comes from the nonprofit group Feeding America. Their vision is “A Hunger Free America.” This aspirational vision describes a highly desirable future in plain language that is clear, memorable, and inspiring.

How does Feeding America pursue their vision? By executing their mission: “To feed America’s hungry through a nationwide network of member food banks and engage our country in the fight to end hunger.” This specific, concrete mission describes what this organization does – builds networks of food banks and engages people through advocacy and awareness efforts. And just like their vision statement, Feeding America’s mission is described in simple, plain language.

While mission and vision statements are often viewed as external marketing materials, they actually have a role to play internally as well. Each member of the team’s daily activities should line up with the mission. If anyone is doing things that do not match the mission, they are unlikely to contribute towards achieving the vision.

Because Mission and Vision statements get to the heart of what a team does and why they do it, it is a good idea to include team members in the process of developing them. This canvas provides an easy way to make sure everyone in your group has a voice in developing these statements.

by dbward | Mar 2, 2020 | Uncategorized |

Today’s blog post is by Allison Khaw, a systems engineer and frequent creative collaborator & co-facilitator with the Innovation Toolkit.

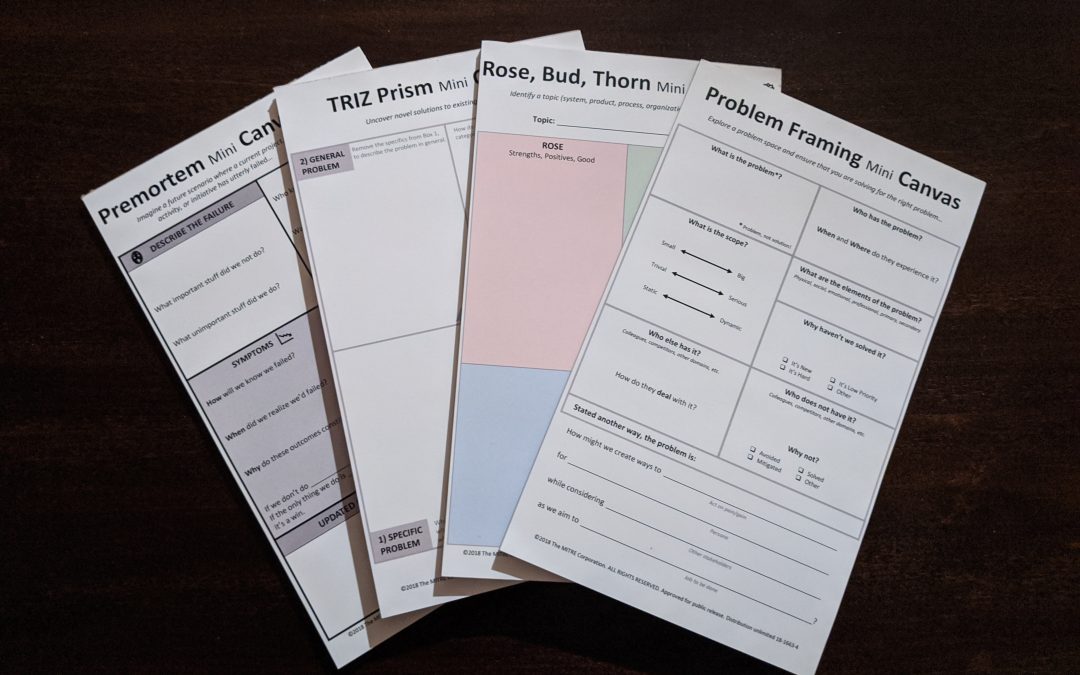

Over the holidays, I received a Knock Knock “Make A Decision” notepad as a gift. It walks you through the decision-making process with just the right mix of realism and levity. This was a perfect gift for me, as I’ve always loved miniature versions of, well, everything. I have a mini book, a mini mirror, and a mini briefcase for business cards in a neat row on my desk, and if you look more closely, you’ll find a handful (literally) of other such knick-knacks too. In my day-to-day job as a systems engineer at MITRE, I model systems on a much larger scale, and yet, this notepad got me thinking… What if the tools in the Innovation Toolkit were represented in a similar format? In addition to the standard large format tool canvases, what if there were… Mini Canvases?

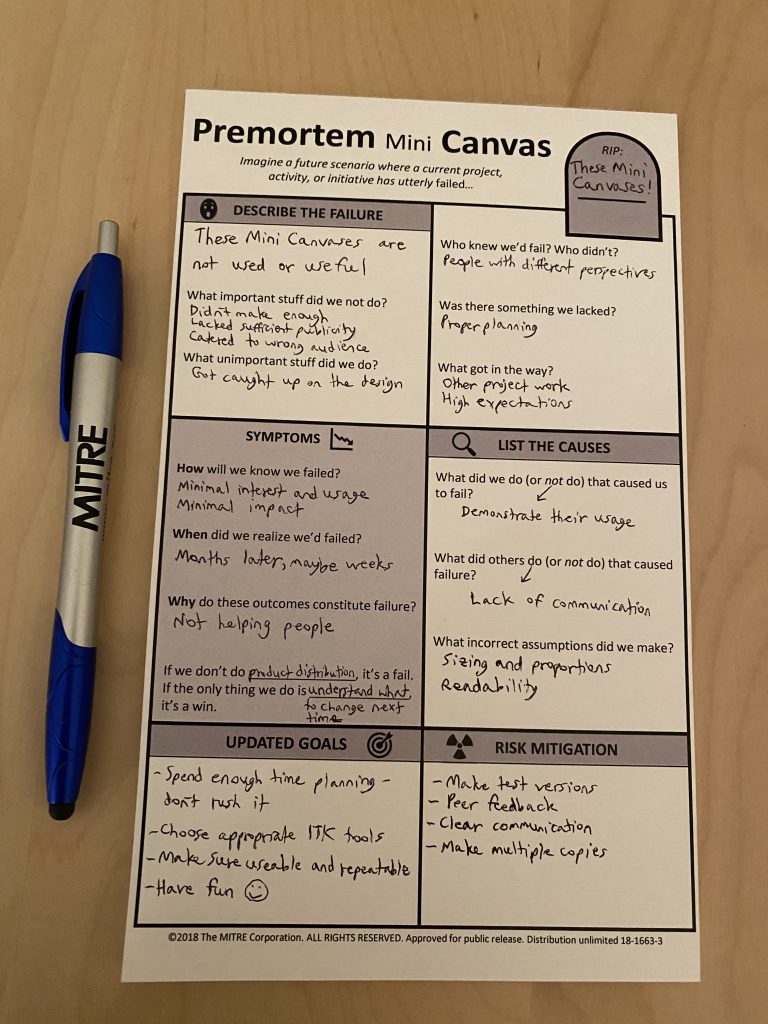

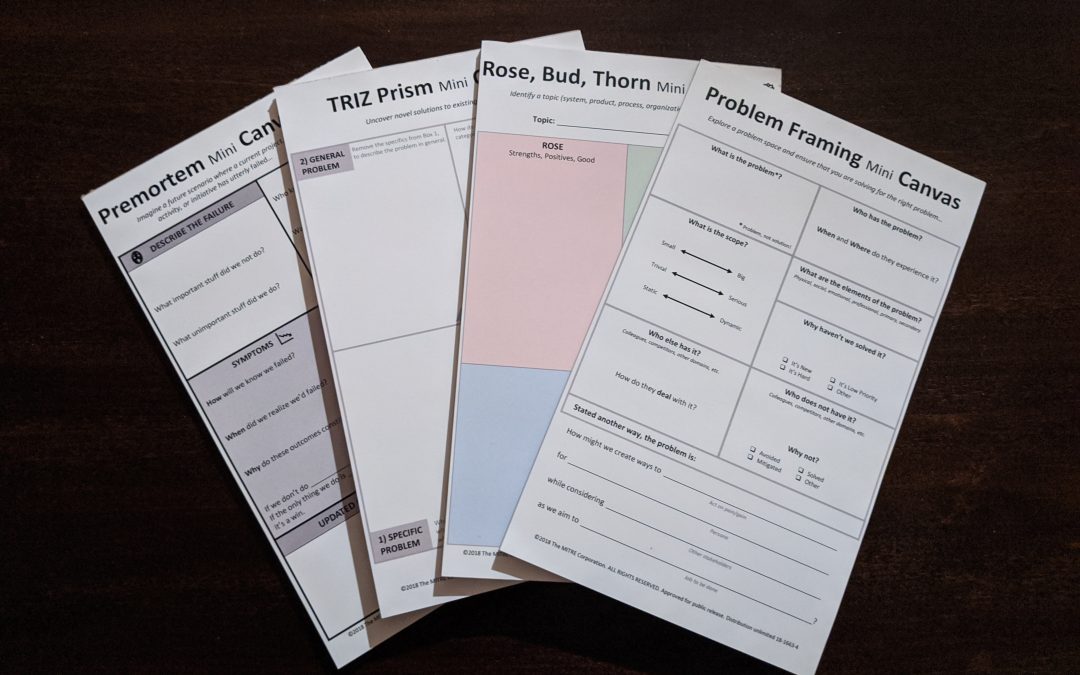

And the idea was born. Four ITK tools – Problem Framing, Premortem, TRIZ Prism, and Rose Bud Thorn – seemed perfect for a first batch. These tools could be designed to fit on 8.5×5.5” sheets of paper while remaining readable. They could then be produced in bulk and widely distributed. Through it all, their power to help would speak louder than their unassuming size…

• Need to frame a problem? Explore a problem space and ensure that you are solving for the right problem with the Problem Framing tool.

• Need to develop a plan? Imagine a future scenario where a current project, activity, or initiative has utterly failed… and explore this scenario with the Premortem tool.

• Need to generate ideas? Uncover novel solutions to existing problems with the TRIZ Prism tool.

• Need to evaluate options? Identify a topic (system, product, process, organization, etc.) for analysis with the Rose, Bud, Thorn tool.

The be auty of these Mini Canvases is that they emulate an innovative mindset. You want to experiment with using the same tool in different ways? You “fail” with your current sheet and want to begin anew? Easy, just rip off the old sheet and use a fresh one. The possibilities are endless.

auty of these Mini Canvases is that they emulate an innovative mindset. You want to experiment with using the same tool in different ways? You “fail” with your current sheet and want to begin anew? Easy, just rip off the old sheet and use a fresh one. The possibilities are endless.

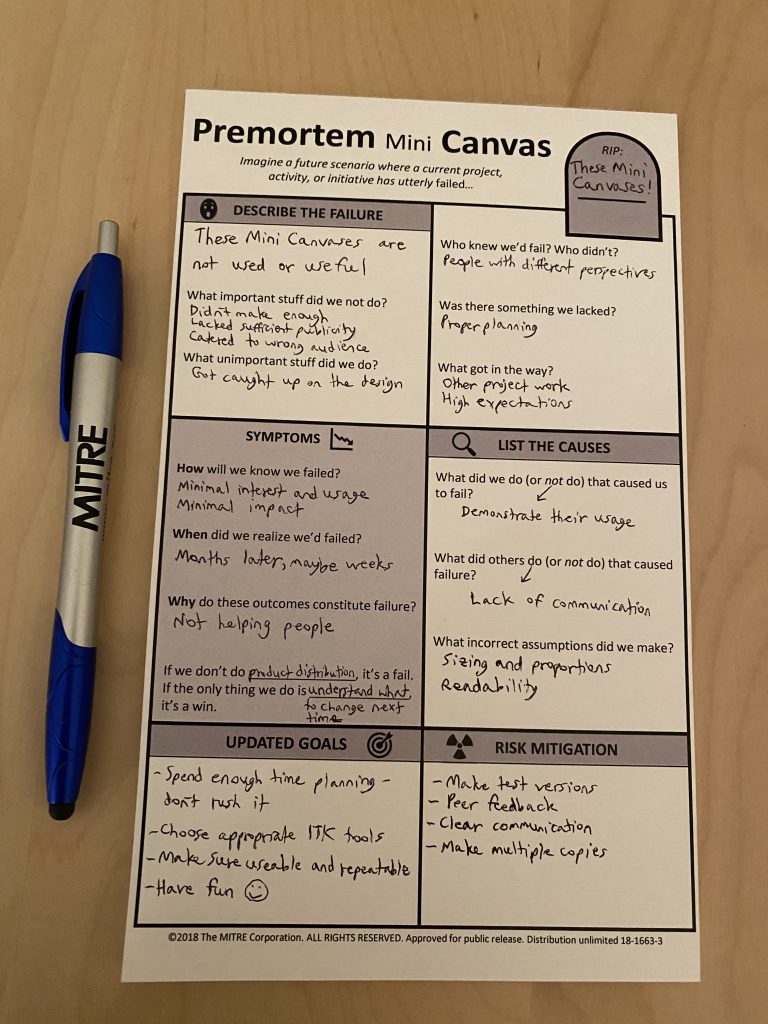

But hey, we practice what we preach. What if these Mini Canvases are not successful? Let’s find out! Here is a Premortem Mini Canvas filled out meta-style (RIP: These Mini Canvases). We’ll use what we discover here to adjust in the future. What about you? What can you change about your own goals and risk mitigation strategies to improve your current products?

Looking ahead, these Mini Canvases will be used as ITK “swag” at conferences and events (stay tuned!). They can serve as effective innovation tools, simple conversation-starters, or both. At the very least, they can sit at your desk, as a playful reminder of the tools at your disposal, if you so need them.

We plan to produce more of them soon.

I never thought that my love for everything miniature would come into play here, and yet it did. So keep an eye out. You never know when inspiration will strike and how far along the innovation path it may take you. Wherever you find yourself, Team Toolkit is ready to help.

– Allison Khaw

We all used to have in-person meetings for collaboration and ideation activities. Then COVID-19 hit. And quarantine. And we all scrambled to maintain collaborations across stakeholders despite the inability to continue in the usual ways. And as you no doubt have noticed, there are critical differences between planning and executing a successful virtual collaboration and the traditional in-person events. It’s not as easy as just doing the same old stuff, but this time on video. We have to make a whole bunch of other changes, and they aren’t easy or obvious. That’s precisely where we’d like to help.

We all used to have in-person meetings for collaboration and ideation activities. Then COVID-19 hit. And quarantine. And we all scrambled to maintain collaborations across stakeholders despite the inability to continue in the usual ways. And as you no doubt have noticed, there are critical differences between planning and executing a successful virtual collaboration and the traditional in-person events. It’s not as easy as just doing the same old stuff, but this time on video. We have to make a whole bunch of other changes, and they aren’t easy or obvious. That’s precisely where we’d like to help.

auty of these Mini Canvases is that they emulate an innovative mindset. You want to experiment with using the same tool in different ways? You “fail” with your current sheet and want to begin anew? Easy, just rip off the old sheet and use a fresh one. The possibilities are endless.

auty of these Mini Canvases is that they emulate an innovative mindset. You want to experiment with using the same tool in different ways? You “fail” with your current sheet and want to begin anew? Easy, just rip off the old sheet and use a fresh one. The possibilities are endless.