by Niall White | Sep 16, 2019 | Uncategorized |

Remember the days of building a sandcastle in a sandbox, or creating a spaceship out of an old egg carton and tinfoil? These are examples of Minimum Viable Products (MVPs) and/or Prototypes!

Perhaps you didn’t have the money to buy the latest Millenium Falcon when you were a kid so you used the resources readily available to you to build something that shared the same vision: The power of space travel in the palm of your hands. This vision likely inspired others to make a similar investment, ask you how you did it, and carefully monitor the groceries brought in from the car. These same principles scale to a real-life next generation space transport, designed to carry a crew to Mars.

In the world of Agile software development, “DevSecOps”, and Design Thinking, its not uncommon to hear the terms Minimum Viable Product (MVP) and Prototype. You may even hear them used interchangeably, but is this correct? Let’s take a look.

An MVP is a product with a minimized feature set, usually intended to demonstrate vision while reducing the developer’s risk. Precious resources are saved by creating a smaller set of capabilities or information. Focusing solely on providing some initial value to users allows developers to test their assumptions and demonstrate basic market viability before making significant investments of time and money.

In some circles, a prototype is a representative example of the desired end-product or service. These can be incredibly useful for demonstration, testing, and getting buy-in from stakeholders. In other circles, prototyping is used for quickly assessing the viability of an idea using lower-than-production-quality materials (ex. using a paper towel roll as a lightsaber handle …). The latter interpretation of prototyping is perhaps more in line with the intended meaning of MVP, as coined by Frank Robinson and made popular by Steve Blank and Eric Ries.

One important thing to note is that both MVP’ing and Prototyping are best done iteratively. Don’t make just one MVP or prototype. Create several, each of which builds on the lessons from the previous ones.

Depending on the environment, it can be important to note the differences. Perhaps you find yourself in an organization where the term “prototype” has centered around the shiny representative final product. If you bring up rapid prototyping to weed out various risks, you may find yourself under the proverbial pile of rotten tomatoes. On the other hand, you may need to be careful using the term MVP. Some may have bad experiences where an MVP was too “Minimum” and not enough “Viable Product,” such that it turned off potential investors.

Can your egg carton be considered a prototype? Certainly! Just remember that there may be some “Doc Browns” out there, apologizing to Marty for the scrappiness of his model of downtown Hill Valley, complete with miniature DeLorean. You may have to explain that your use of “prototype” is not the same as a production ready representative example.

Follow these links if you’d like to learn more about MVP’s and Prototypes.

by Niall White | May 6, 2019 | Facilitation Tips

Using an innovation toolkit can be difficult in a classified environment. There may be restrictions on what information can be shared, where it can be stored, and who it can be communicated with. What do you do with the notes? What if someone says something they aren’t supposed to say? Is there the right level of system access to present the appropriate slides? Are creativity and innovation inherent aspects of a culture in a classified, secure workspace?

These and other questions may be asked when considering innovating in a classified environment. The short answer is: Yes! You can certainly innovate in such an environment. It may require some creativity and flexibility to pull it off.

Let’s make up a scenario: You feel that your team isn’t considering all the alternatives for a given decision. You are aware of some ideation activities and wonder if you could facilitate an innovation activity with your team. You start thinking about the secure environment you work in. Your mind begins to fill with doubt as you ask yourself about all the hurdles you’ll have to jump over to pull this off. Questions like: Who would I invite? What level of classification would the discussion be held at? What if our notes can be compiled into an even higher classification level that the room isn’t accredited for (let alone the clearance levels of the attendees)? Is there a computer in that room with access to the network required to present certain slides? Are cameras allowed? Do I know the new security classification guide (SCG) well enough to facilitate the discussion? What will I do with all of those sticky notes and poster boards when the meeting is over? Do I need to find an official courier to get the notes to a different facility?

This may be a scenario you can relate with. It’s not easy to answer all of these questions, especially when these activities may be new to your organization. Here are a few tips for pulling this type of exercise off:

Don’t overthink it

It’s easy to overcomplicate an idea to the point of never seeing it through. If this applies to you; simplify. Sometimes, getting people in a room where they feel safe to talk about potentially unpopular ideas is half the battle. There is a first for everything and if people feel heard then the power of diverse thinking can run its course.

Set clear goals

It may require some effort to get management on board (or not, depending on the culture of your organization). An innovation workshop could pull important people from their important tasks. This is why you need to clearly communicate the goals of your meeting/workshop. This will also help you to organize and facilitate the event, as you will have a constant reminder of what you are actually trying to accomplish.

Communicate early, communicate often

In general, your leaders may not appreciate being surprised about an event they didn’t know about (and that cost them precious resources). If you think this may apply to you, communicate your idea early on. It might be wise to start with an immediate supervisor, as they may have a working knowledge of available resources, etc. Finding a champion amongst your team can also help “sell” the idea. Provide examples of similar organizations performing similar activities. You could even tie your activity into an industry-accepted activity that your organization regularly employs.

Plan for success

If you are concerned that your discussion/notes may result in classified information, plan for it. Reserve a space that can handle the highest classification level you think the conversation and/or notes may go to. Only invite people that have that access. Coordinate with your local security representative to make sure the room is ready, the people are cleared, and that you have a plan for the written material that may leave the meeting and need to be stored. If possible, invite someone strongly familiar with the SCG to give a short SCG overview. In lieu of an expert, the SCG itself should be on-hand for reference. If anything will be related to Intelligence, invite your local Intelligence representative to not only give a short presentation (e.g. a threat briefing) at the beginning of the workshop, but to participate as well.

Use appropriate tools

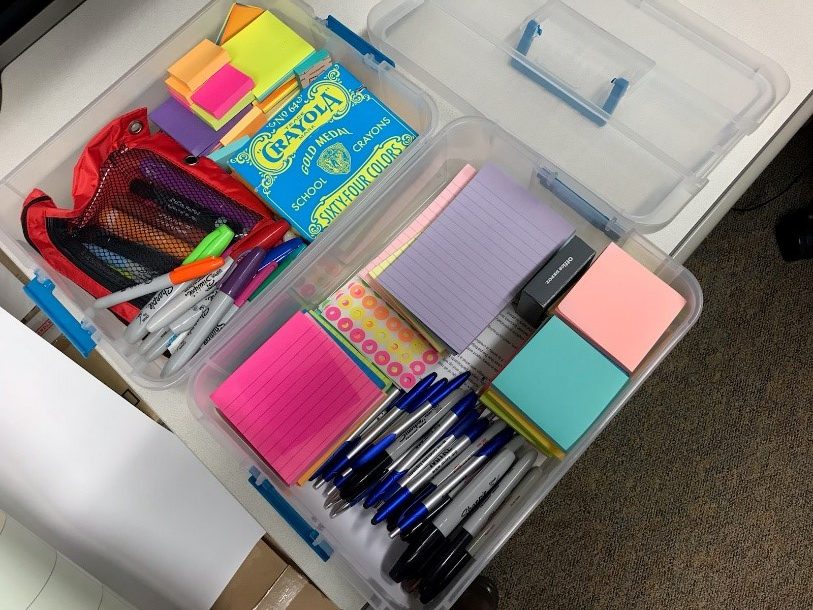

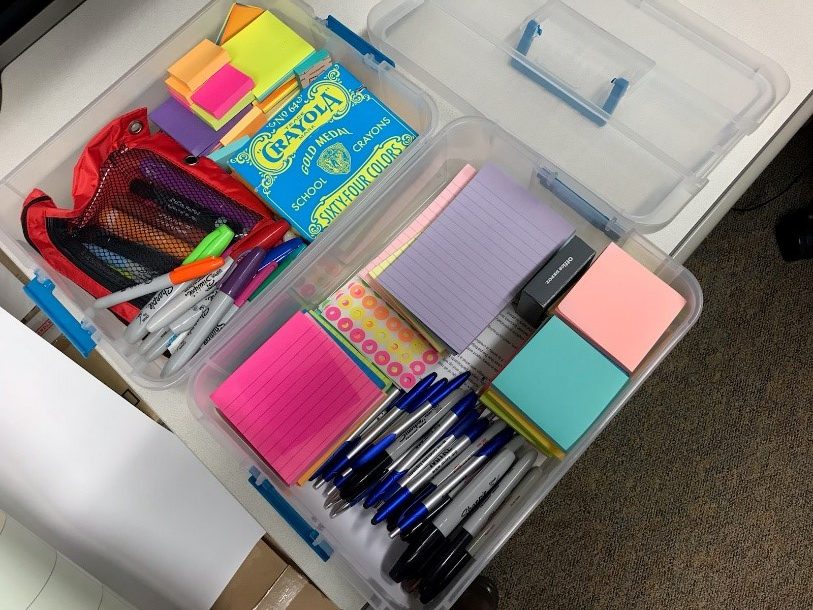

You may feel the need to provide high fidelity presentation, facilitation and/or note-taking material. While this can certainly be helpful (slides, markers, posters, toys, etc.), don’t let it bog you down to the point of not doing the activity at all. Getting authorization to run certain software may be a bridge too far. In addition to having a licensed copy of the software purchased and ready, there is also a need to have an authority to load and operate the software. In short, in addition to pen & paper, plan on only having the office automation applications available in the facility. If you can get some sticky notes, paper, and a handful of colored sharpies, call it a win.

Expand the buy-in

You don’t want to do this in a vacuum. Ask people how they would like to contribute. Bring in some diversity of thought. Allow people to do what they are the best at. This creates more buy-in while also having a second set of eyes review any policies or procedures you aren’t sure about.

Is it always easy to pull this off? Probably not. Still, as you try and show the fruits of your efforts, your organization could recognize the positive change and embrace similar techniques going forward.

by Niall White | Mar 18, 2019 | Facilitation Tips, Tools 101

As we wander around and share ITK with people, we get a lot of questions. In this week’s post, we’d like to share some answers to the more frequently asked questions. Don’t see your question here? Send it to us in an email (ITK@mitre.org) or post it in the comments section.

Q: Where do I start?

Fortunately, there are many options to choose from! Ask yourself if you want to ideate and generate or evaluate and consolidate. From there, you can choose tools that will assist you accordingly. In general, there are tools that assist in divergent (ex. “Lotus Blossom”) and convergent (ex. “Stormdraining”) thinking.

Q: How much time will I need?

From formal day-long workshops to “notes on a napkin” dinner discussions, the ITK tools can be used in a variety of settings. A System Map, for example, may be used for a small, simple process involving few relationships, no competition, and little policy, requiring little time to complete. It can also be used for a multi-organizational operation that involves thousands of stakeholders and dozens of competitors. This would obviously take much longer to complete.

So timeframes vary based on your needs, constraints, and objectives. Give yourself enough time to really dig into the processes and seek a diversity of thought. On the other hand, don’t be afraid to hold your own mini workshop at your desk when you only have a few minutes. In general, you will get as much out of these tools as you put into them, but they are highly adaptable to your specific situation.

Q: Why put structure on creativity?

Being creative doesn’t just mean brainstorming or randomly throwing ideas on a whiteboard (though these can be pretty helpful practices!). We’ve found that providing some structure to your process can help teams produce higher quality ideas in less time. These tools focus our creativity on the problem at hand, rather than having to invent the method as well as the solution.

Most of the ITK tools really come down to asking the right questions at the right time. They help unlock creativity, uncover hidden assumptions, and build consensus. For example, When prioritizing the stakeholders in your system, you may just make a list and start prioritizing. Using a Community Map, however, gives you steps to identify allies, audiences, and influencers, prioritize them based on a set of criteria, and then take specific actions to move forward.

The other big benefit is that most of the tools result in a sharable artifact that documents the creative ideas your team came up with.

Q: What resources will I need?

It sort of depends on which tools you choose and what setting you’re in. However, in most cases you will generally need: the right minds (get the right people in the room), a physical space conducive to your activities, any needed materials (markers, sticky notes, whiteboards, tables & chairs, a camera, handouts, etc.) and a workshop outline (doesn’t need to be anything formal; just a plan of what you want to accomplish and how).

Check out a previous blog post for more details about the workshop facilitation kits we use.

Q: When should I use these tools?

All the time! These tools can be used for framing problems, understanding users, and generating ideas early in the process of launching a program. They can also be used for evaluating options, developing plans, reducing complexity, and other later-phase tasks.

Each tool description includes a short explanation of When to use it, but the truth is most of them can be used at any time. As a general rule, it is good practice to start using them earlier in a project rather than later, as you may identify artifacts pivotal to your course of action. Need help picking the right tool or the right time? Drop us a note at ITK@mitre.org and we’d be glad to talk you through it.