by dbward | Jun 20, 2022 | Misc Awesomeness

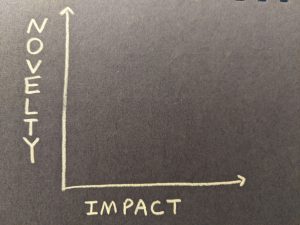

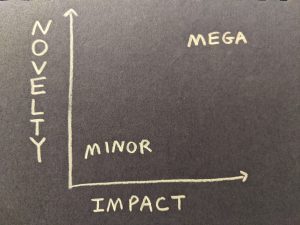

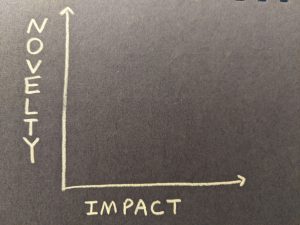

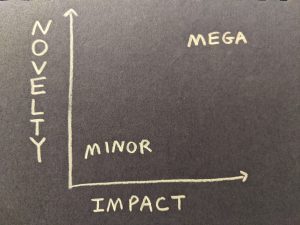

Here at ITK, we define innovation as “novelty with impact.” Just last week, it occurred to me to turn that definition into a graph, with Novelty along one axis and Impact along the other (seriously, how did I not think of this sooner?). At the low end of the Novelty axis, we find things that are Kinda Familiar, while at the high end things are Utterly Unique. Similarly, things at the low end of the Impact axis are Kinda Helpful, while the high end is full of products and services that SAVE THE WORLD.

So, the lower left quadrant might be minor innovations, things that are both kinda familiar and kinda helpful. The upper right quadrant is mega innovations. Both quadrants are innovative, just to different degrees. So far, so good, right?

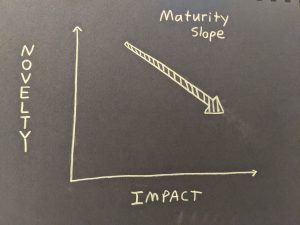

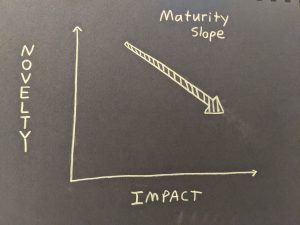

OK, the really interesting thing isn’t in either of those quadrants. Instead, it’s this arrow that points down and to the right. I call it the Innovation Maturity Slope, and it shows what happens when an innovative product or service becomes… popular (so maybe we should call it the popularity slope?).

OK, the really interesting thing isn’t in either of those quadrants. Instead, it’s this arrow that points down and to the right. I call it the Innovation Maturity Slope, and it shows what happens when an innovative product or service becomes… popular (so maybe we should call it the popularity slope?).

Here’s what’s happening along this slope: popularity leads to familiarity, which reduces novelty. People see the thing and respond “Oh yeah, I’ve heard of that.” But popularity also means more people benefit from the thing, which means impact increases.

Here’s what’s happening along this slope: popularity leads to familiarity, which reduces novelty. People see the thing and respond “Oh yeah, I’ve heard of that.” But popularity also means more people benefit from the thing, which means impact increases.

The net result: popularity moves us down and to the right.

Think of what happens to an iPod, a cool new app, or the latest software development method. At first, a small number of early adopters use the thing, so it is relatively uncommon (high-N) and its impact is constrained to a relatively small group (low-I). It sits in the upper left quadrant. But later, everyone gets an iPod, discovers the app, or adopts Agile software methods. As more people use the thing and benefit from it, it becomes less novel but more impactful.

The reason I’m sharing this is to point out: this change can feel like a loss to the person behind the innovation. It might even feel like a failure, as if they “aren’t innovative anymore,” because their creation is less novel than it was before. It’s super easy to mistake a drop in novelty for a lack of innovation, even when impact is increasing. But the thing to remember is that novelty is not the point. For that matter, innovation isn’t the point either. Impact is the point – doing something that matters, solving a problem, creating value, helping people, making things better.

So if you are fortunate enough to see your project move to the right along the Impact axis, remember to count that as a sign of maturity and progress. It’s definitely a win.

by dbward | Jun 16, 2022 | Facilitation Tips, Misc Awesomeness

Team Toolkit is excited to announce that WE WROTE ANOTHER BOOK!!

It’s titled The Innovation Toolkit Handbook. In this book, several members of Team Toolkit share our specific practices and processes as clearly and directly as we can, along with some reflections on why we do what we do the way we do it. It’s not exactly a sequel to our first book. Instead, we think the characters from our first book would have wanted to read this one. Basically, this handbook takes you behind the scenes and fills in some gaps the website and first book don’t cover. You’ll find chapters about Team Toolkit’s culture, our certification process for new facilitators, and our method for developing new tools. We also share tips on how to use the tools, perspectives on failure, and commentary on a collection of adjacent topics that don’t quite have a home on our website.

You can get the PDF version for free right here. It’s also available as a paperback for $8.35 (plus shipping).

by dbward | Jun 6, 2022 | Facilitation Tips, Misc Awesomeness

This week’s post is by Manya Kapikian and Bill Donaldson

Eyes sparkling, front paws down, stick in mouth, a tail that’s wagging like a helicopter propeller at warp speed. That’s what my dog does when he indicates he’s ready to play. At 7, he’s a mature adult dog with a sense of curiosity, wit, and zest for life.

Associated as a part of childhood, human adults seemed to forget what their animal counterparts have not. Play is an activity that is never to be outgrown. Stuart Brown, author of Play, talks about how play helps children develop as individuals and members of a society. For children, play offers the opportunity to learn and grow, while having a bit of fun along the way. Many adults, on the other hand, are missing out on that benefit.

Brendan Boyle, Founder, IDEO Play Lab wrote: “Work doesn’t have to be serious to be impactful. In fact, we tend to get our best ideas when we break out of the usual routine and have a little fun.”

And so, play became a topic of conversation during a recent Lunch and Learn. The ITK facilitator asked the group: how do you increase play and playfulness during a meeting to increase innovation?

There were many activities that came up during the discussion. Some could be done virtually while others required everyone be in the same room. Here are a few of our activities that were successfully used as captured from the meeting that we’d like to pass along to you:

Rock, Paper, Scissors. If you are looking for an in-person activity, nothing brings out the best of a competitive spirit than Rock, Paper, Scissors. To learn how to play, visit The Official Rules of Rock Paper Scissors. Tip: Whoever loses, becomes the winner’s best friend. By the time you get to the end there’s two people in the room with a fan base behind them. (Warning: This can get loud!)

Group Thumb War. (Yes, this is exactly as it sounds and we can’t wait to try it!). Another in-person group activity. It is based on Jane McGonigal’s book Reality is Broken and to get a sense of what a room full of people thumb wrestling is like, check out the TED video Massive Multiplayer Thumb Wrestling

Animal Sketch Competition. This can be done either in-person or virtual. An excellent energizer, especially before activities like a design studio. It requires a pencil/pen and some paper. A moderator picks out an animal for participants to sketch. There are 3 rounds of sketching the same animal. Each round gets faster and faster – 1 minute, 30 seconds, 10 seconds. The group picks the winning sketch. The artist of the winning sketch gets to pick the animal for the next round.

Music Playlist. This can be done either in-person or virtual. Have a playlist or theme of the day and associate it with music. Play at the beginning as people are coming into the room and close the meeting with a song or two once business is done.

Why were these activities a success?

They were successful because they helped people relax and get into their creative zone. Let’s take the animal sketch competition. Our colleague Jordan uses that often when he starts a design session. He explained,

“You ask them to draw out a cat and it’s amazing how creative people get quickly. By the time they hit round 3, where it’s 10 seconds, people are fired up. They’re laughing. They’re playful. It’s a quick way to get a group in a more fun headspace. It’s a little bit like warming up before exercising right like you’re stretching you know the creative muscles and flexing a little bit and that when you so when you do go into an activity. You are over that hurdle of ‘I can’t sketch anything’ because everybody clearly did 3 rounds of sketching.”

Try it out!

To inject a little bit of play at work requires a little bit of thought and foresight. It could depend on the group, the topic at hand, how much time do you have. An activity can take a few minutes, or even seconds. The examples we gave may take a few minutes. It can also take a few seconds by simply asking everyone picking to pick an emoji or a picture that best describes their mood.

There’s a world of play waiting to be discovered. Below are additional resources. Leave a comment, we’d love to hear about what’s worked for you!

Additional Resources:

Photo credit: Takashi Hososhima

by dbward | May 31, 2022 | Misc Awesomeness

When was the last time you made something? Specifically, when was the last time you made something to share?

I’m not talking about a sandwich or a drink. I’m talking about a creative artifact you can pass along to someone else, so they can use it, learn from it, or be inspired by it.

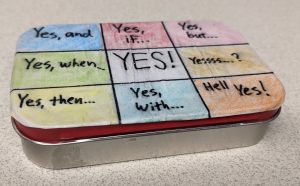

OK, maybe a really good sandwich could fit that bill, but really what I have in mind is a sketch. A photo. A framework. A video. A new tool. A variant on an existing tool (like the X-blossoms or the mini-canvases). Or even an X-blossom decoupaged onto an empty Altoids tin.

We often describe the ITK community as having a “maker culture.” We love to noodle around with prototypes and sketches, building Minimum Viable Products out of cardboard and duct tape. So this post is a friendly reminder and personal invitation to put that cultural attribute into practice. If it’s been a while since you made something, I encourage you to make it a priority… to make something today.

Not sure how or where to get started? Click on a few of the links in this blog post and see what sort of creative ideas jump out at you. And if time is short, then set a timer for 5 or 10 minutes, and see what you can make before the buzzer goes off. You just might be surprised!

And of course, don’t forget to share the results of your creative efforts with someone.

by dbward | Apr 4, 2022 | Facilitation Tips

This week’s blog post is by guest bloggers Manya Kapikian and Jackie Vessal

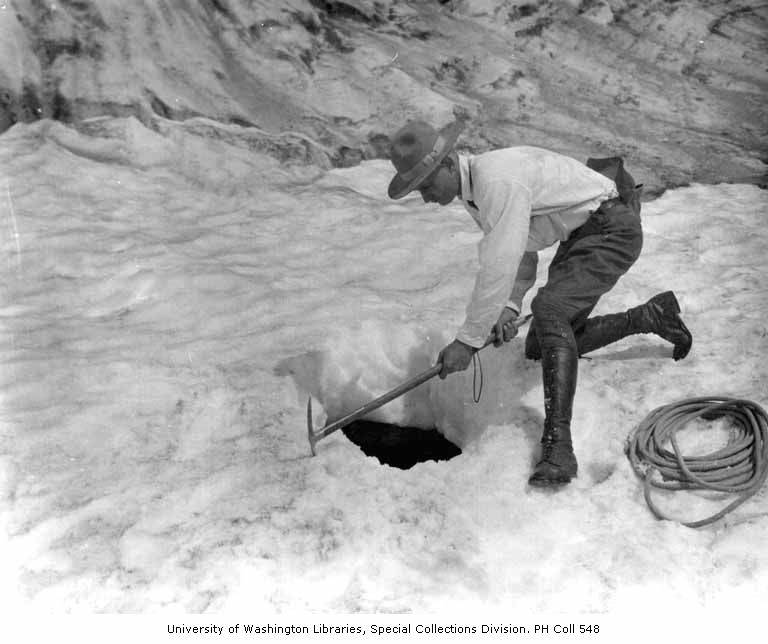

It’s Thursday and you are logging into a meeting with people you don’t know. The agenda starts with an icebreaker and the invite asks everyone to bring their favorite mug. What is your reaction? Do you cringe, or do you enthusiastically bring 10 mugs?

The “Mug Show & Tell” exercise is a common icebreaker, in which people get to share a little bit about themselves. Why do we do this? Authors Frische and Green explain the benefits of icebreakers in their article, Make Time for Small Talk in Your Virtual Meetings. This practice is particularly important these days, where our virtual or hybrid work environments no longer present the same opportunities for casual chatting.

Icebreakers are designed to help members of a group warm up, to get to know each other a little and build a sense rapport. An icebreaker can be particularly helpful for a group of people coming together for the first time, but even an established group may find these activities helpful.

Of course, not everyone enjoys these activities. Google “I hate icebreakers” and you’ll find plenty of stories about people who cringe at the thought of participating in an icebreaker. They can be awkward for introverts, can create tension and anxiety, and easily feel forced. Some people see them as frivolous waste of time and too touchy feely. But as Frische and Greene explained, there is a case to be made for doing them anyway.

Icebreakers open a communication channel that helps people relax, get to know one another, and make it less awkward to interact. They are an effective way to network and meet new people. In a meeting, conference, or other event where strangers need to come together, icebreakers help individuals to “break the ice.” They allow for complete strangers to interact, get to know one another, and begin to form a common ground. Once folks start talking, it becomes easier to keep the conversation going. A good icebreaker can set the tone and mood for the rest of the meeting or conference.

It is important to make sure your introductory activity is not too long. Ideally, it should last between 5 and 10 minutes – just long enough for people to feel comfortable and ready to discuss the key topics of the meeting.

The type of icebreaker you chose will depend on if you are in person or in a virtual setting. Whatever the setting, the best icebreakers are interactive and memorable. If your space allows, plan on an icebreaker that gets people moving around the room. If meeting virtually, break up your audience into more intimate groups. The group size should be 2-5 for small meetings and 6-10 for large meetings. To make an icebreaker memorable think fun, get them laughing and having a good time.

Lastly, be creative. Go beyond your first idea and aim to customize the icebreaker experience to your group.

Try one of these at your next meeting.

- Ask everyone to answer one quick question. Offer them 3-5 questions and a time limit of 30 seconds to a minute. (Alternatively, turn these questions into a poll so that the only thing a person must do is click a button.) Some questions that our teams have enjoyed included:

- Would you rather live without music or live without TV?

- Tell us how you are feeling today in the form of a weather report

- If you could rid the world of one thing, what would it be?

- What TV advertisement bothers you the most?

- Assign a quick task and have them go around for a minute and so and talk. Examples of tasks:

- Ask people to bring their favorite mug

- Wear your favorite concert t-shirt

- Wear your favorite hat

Ice breakers are simply a way for people to warm-up to each other and get into a zone for collaboration quicker. Ultimately, they are a small investment to achieving a better meeting outcome, and perhaps with a little bit of fun sprinkled in. So, maybe the next time someone asks you to bring a favorite mug, consider having one in each hand.

Photo credit Lawrence Denny Lindsley

OK, the really interesting thing isn’t in either of those quadrants. Instead, it’s this arrow that points down and to the right. I call it the Innovation Maturity Slope, and it shows what happens when an innovative product or service becomes… popular (so maybe we should call it the popularity slope?).

OK, the really interesting thing isn’t in either of those quadrants. Instead, it’s this arrow that points down and to the right. I call it the Innovation Maturity Slope, and it shows what happens when an innovative product or service becomes… popular (so maybe we should call it the popularity slope?). Here’s what’s happening along this slope: popularity leads to familiarity, which reduces novelty. People see the thing and respond “Oh yeah, I’ve heard of that.” But popularity also means more people benefit from the thing, which means impact increases.

Here’s what’s happening along this slope: popularity leads to familiarity, which reduces novelty. People see the thing and respond “Oh yeah, I’ve heard of that.” But popularity also means more people benefit from the thing, which means impact increases.