by dbward | Jun 29, 2021 | Uncategorized

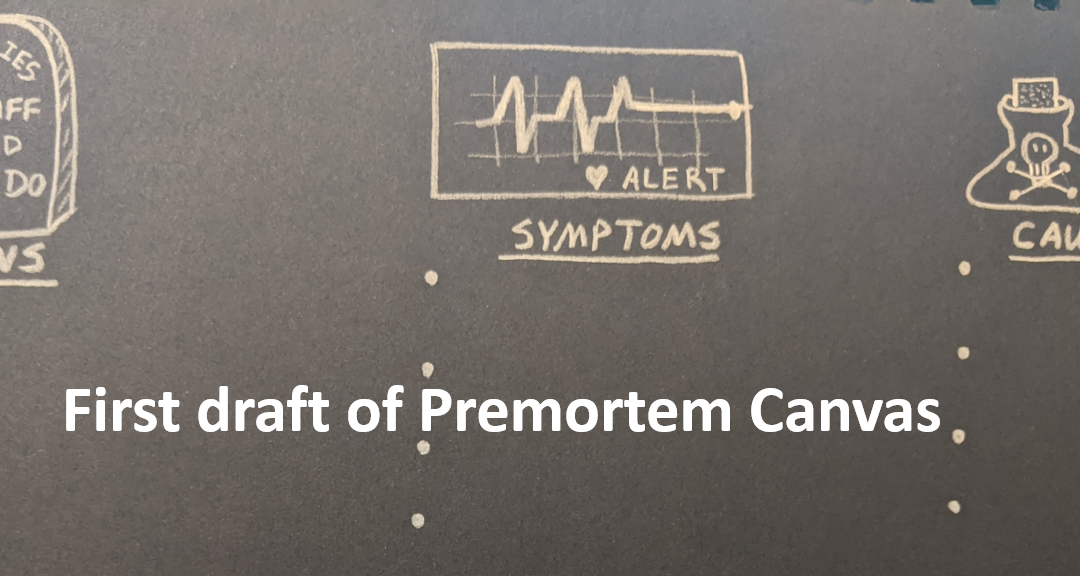

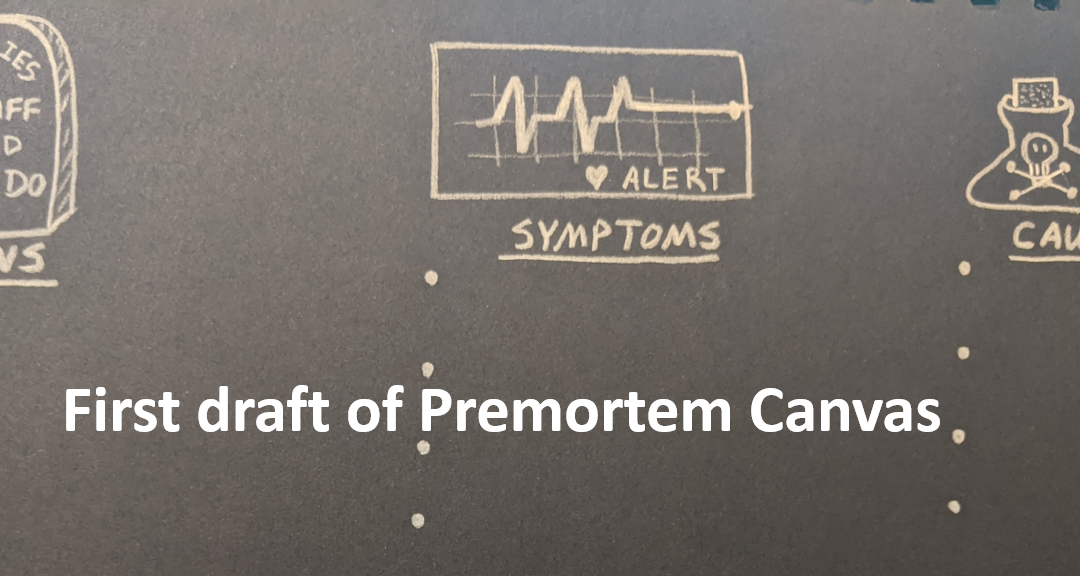

Tools like the Mission/Vision Canvas, the Problem Framing Canvas, and the Premortem tool all help teams develop a brief statement of some sort. It’s a pretty good feeling when the group comes up with a formulation or a phrase that they all agree on, and the statement itself can be a really helpful foundation and guide as the project or effort moves forward.

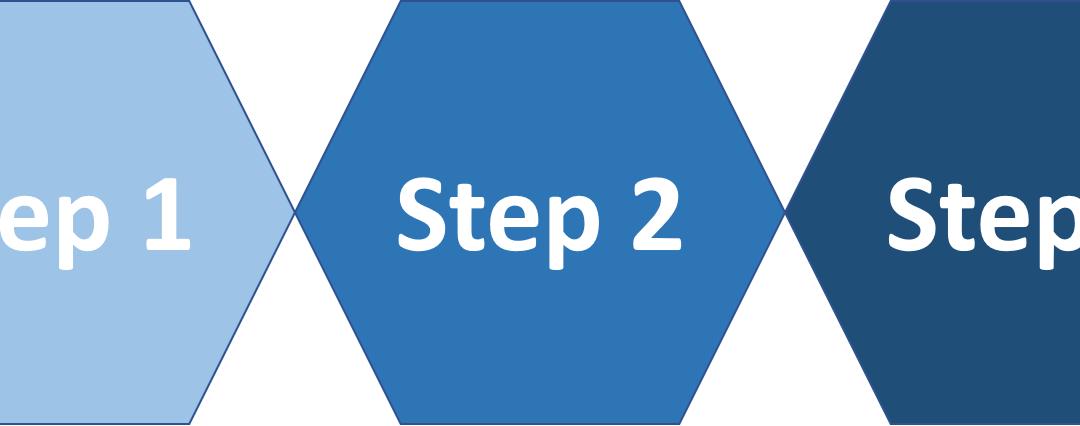

However, the work isn’t necessarily complete once the session ends and consensus has been reached. The group may have a pretty good version of a Vision Statement or a Problem Statement, but what they do next will determine how effective that statement is. I recommend a three-step process that looks something like this.

- Sleep on it. Set the statement aside and come back in a day or two with fresh eyes. You may discover it’s not as clear and clever as it seemed at the time. You may uncover a gap or a friction point, an opportunity to improve it… or you may confirm that it’s exactly what you hoped it would be.

- Socialize it. Share it with some colleagues who were not in the session and get their perspectives. Ask if it resonates with them – is it clear, accurate, actionable, etc? Testing it out and validating / refining the statement doesn’t have to take long or be super formal. In fact, it’s probably best if it’s quick and informal.

- Wordsmith it. Continue to play around with word choice and word order. Might the statement make more sense if you shuffled some parts around, swapped in a synonym, or made other changes? Sleeping on it and socializing it may unlock some new ideas you didn’t come up with in the original session.

As much as an ITK session aims to develop “clarity and consensus” on topics, keep in mind most of this work is actually iterative. We hardly ever follow the one-and-done path, and we like to remind people that there is a zero percent chance we got it one hundred percent correct on the first try. As a general rule, we get the most of out ITK sessions when we think about them as the beginning of a conversation rather than the end of one.

by dbward | Jun 14, 2021 | Uncategorized

Today’s blog post is from Jeffrey Hammer, one of ITK’s new trainees

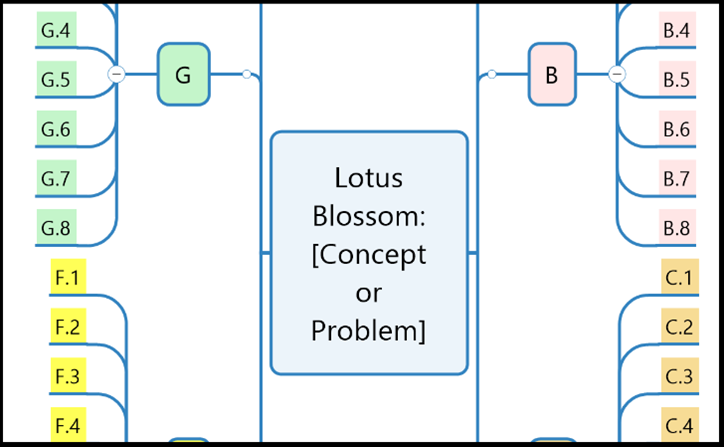

If you’ve seen the ITK tools, some of them may look familiar. Lotus Blossom? That’s brainstorming. Stormdraining? Organizing a brainstorm. Mission and Vision Canvas? Companies have been defining their vision and mission for years, with one of the earliest known mission statements going back to 1941 in the American Journal of Economics and Sociology. So why ITK?

The answer for me lay in two areas. First, the tools facilitate these common processes in a different way. I thought I was an experienced brainstorming facilitator, even integrating mind maps in my sessions as far back as 2000. Lotus Blossom upended that thinking and gave me an entirely different way to approach a brainstorming session. The design of the tool itself, combined with the facilitation guide, invigorates fresh thinking. Mission-Vision uses plain language questions and leads a team down a path that eventually culminates in a mission or vision statement without you even realizing it.

Second is the ITK philosophy. There is an energy and culture behind these tools that its creators have infused into their design and use. It’s a positive, experimental, nurturing culture that encourages the novel thinking needed for innovation. That philosophy radiates from the founders and ITK evangelists, and is infused not only in the tools themselves but also how they can be applied to maximum effectiveness. And they are fun! Every tool I have used with a team has been met with enthusiasm and satisfaction.

As newbie and (hopefully) soon to be minted ITK Certified, I continue to learn and grow with each new experience. If you can embrace the novel approach these tools offer to scoping, designing, understanding, generating, and evaluating problems and ideas, it will take you and your team’s thinking to a whole new level.

by dbward | Jun 7, 2021 | Uncategorized

As you’ve probably noticed, the ITK website has a whole new look and layout! We’ve redesigned all the tools, added lots of new content and material, and even made it easier to filter through the tools to find just the one you need.

We hope this refresh makes the site easier to navigate and use. As with any design effort, it’s an iterative process so we’d love to hear your feedback and suggestions!

by dbward | May 17, 2021 | Tools 101

As MITRE’s Innovation Toolkit continues to evolve and mature, we’ve been reflecting on how we create new tools (and update existing tools). The short version is we do it iteratively. For the longer version… read on!

Most of the tools you see on our website are actually version 7 or version 15 or version 382. The point is pretty much all of them went through considerable modifications on their way to the version you see on the website.

Except maybe the Lotus Blossom. Pretty sure that one popped up fully formed, like Athena from the head of Zeus.

Aside from that single exception, all the other tools are the result of an ongoing series of prototypes and experiments. Sometimes we’ve even used one tool to develop another tool… then updated the first tool based on our experience developing the second one. It gets pretty meta around here sometimes. While that may sound a bit convoluted, we actually have a pretty straightforward way of describing the tool development process. It’s built around a theater / tv show metaphor, and it goes something like this:

An idea for a new tool starts in the Café, where one or two people begin sketching out a rough idea and produce an initial incomplete draft. Maybe they have a casual chat with someone at the next table over, or maybe they have their headphones on as they draw and sketch and write. In Broadway terms, this is where Lin-Manuel composes that first rap and starts laying out the overall structure of Hamilton.

Alexander Hamilton

Next, we move to the Writer’s Room. This is where a group gathers to co-create the tool and further develop it from the Café version. They play with phrases and formats, identify and address gaps in the tool. The idea is for the initial instigator to bring in some collaborators who help transform the incomplete idea into the first complete draft. In the world of musical theater, this might be where a lyricist brings in a composer (or vice versa), or a writer brings in a co-author.

Next is a special type of casual rehearsal called a Table Read, where we test a basic version of the tool with people who weren’t involved in creating it. The point here is to invite new perspectives & contributors. To use Hamilton terms again, this is where Leslie Odom Jr shows up and the writers get to see how the lines actually sound when the actor says them (and continue to rewrite the lines based on that observation & discussion).

Eventually we get to the Dress Rehearsal, where a complete version of the tool is used in a closed environment, to really put it through its paces… without an audience. Unlike the table read, in our dress rehearsal our focus goes beyond the tool itself and now includes facilitation techniques and logistics. In our theater metaphor, this is where the script is basically locked down and the director confirms the lighting, blocking, and choreography.

Then we come to Opening Night, the first time the tool is used with an external group, sponsor, etc. This is still an opportunity to test & evaluate & modify the tool, so we’re all watching and taking notes about changes to make in the next version.

The Full Run means the tool is field-tested, polished, and proven. We might make some small tweaks at this point, adjust the choreography slightly or make little tweaks to the dialogue, but by now the thing is pretty much solid & we can do 8 shows a week. As an added bonus, the understudies get opportunities step on stage… and the writer goes back to the café.

As you see, like a Broadway show, developing a new ITK tool is generally an iterative, collaborative process. One person can instigate and take a certain degree of ownership for a tool, one person can shepherd it through the whole process, pick co-authors and hold own auditions, etc. But nobody has to write / produce / sing / dance / etc in a one-person performance. There are plenty of people available to lend a hand and help transform the spark of an idea into a big hit…

by dbward | May 10, 2021 | Facilitation Tips, Tools 101

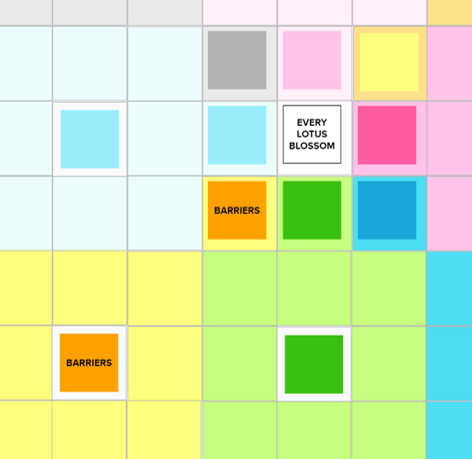

No two Lotus Blossoms sessions are alike, because that particular tool is designed for maximum flexibility and broad applicability. You can do a Lotus Blossom around a problem statement or to explore solutions. You can use it to design an organization, outline a research paper, or define a business process. I’ve even been known to plan out my New Year’s Resolutions in a Lotus Blossom. The options truly are endless, and so is the variety.

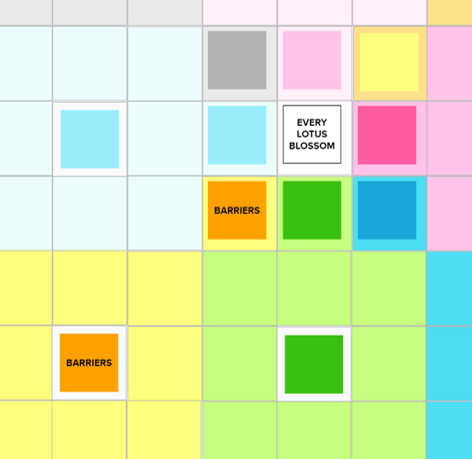

But for all the different ways to use a Lotus Blossom, there is one consistent practice I apply almost every time. It’s a particular petal that seems to fit every situation, regardless of topic or situation. I call it… the Barriers Petal.

It’s a pretty simple concept – just write the word Barriers in one of the petals around the central blossom. I tend to use the lower-left petal of the central blossom, for no particular reason other than that box tends to be available. Plus, having a consistent location helps me remember to do it.

Oddly, one of the things I like about this is the way this brings a slightly negative tone to the conversation, an off note to the composition. While the rest of the blossoms are typically full of possibilities and sparkly ideas, the Barriers blossom helps us anticipate the things that might undermine our plans or interfere with our goals.

This contrast sends a subtle signal to go beyond the obvious, front-of-mind ideas, and to dig a little deeper. Plus, virtually every topic has some sort of barriers associated with it, and it’s better to think about them and anticipate them in advance than to be surprised when one smacks us in the face.