by Aileen Laughlin | Dec 3, 2019 | Interviews |

This week, ITK is chatting with Daniel Hulter who we came across on LinkedIn. On separate occasions Dan Ward and I saw Daniel’s posts and were inspired to reach out and connect. One of Daniel’s recent posts asked the community about upskilling and training personnel so they can be empowered to more proactively solve problems. In addition to hosting a fantastic open discussion, we learned that Daniel is not only encouraging the larger community to make progress in this area but also works with his local base to enable, encourage, and empower personnel. His passion for empowering people and making problem solving approaches/methodologies accessible is something we at ITK feel strongly about as well so we wanted to learn more.

A: Tell us about yourself – what would we NOT be able to find on your LinkedIn profile.

Something that is likely not readily apparent on LinkedIn is the fact that I am deadly serious about what I’m sharing there. I also desperately need to find joy in my work, so I sometimes write on serious subjects in a way that amuses me. I love to laugh, but am pulled perpetually in by the gravity of realities more serious than I think most people want to face every day.

None of what I am would be possible without my wife Jessica, who has sacrificed an incredibly unfair amount to ensure that I can be functional, stay sane, and dedicate myself to the work that I care about while she battles school districts, doctors, insurance gremlins, and children, to ensure our two children can thrive to the best of their abilities. Our 14-year-old daughter Rebecca has been severely disabled since she was born. My wife has had her aspirations on hold for as long as I’ve been in the Air Force, and that lends a certain degree of gravity to me making the most of my time here. I think sometimes people wonder why I’m cranking it up to eleven with the whole ‘empowering Airmen’ routine. The truth is that having a voice and being empowered to spark change is an extremely personal cause for me. I am simultaneously more sincere and more just kidding around than I think most people realize.

A: I know you do a lot of writing and share via your own blog, what was the catalyst or genesis for starting to do this? What article do you think has resonated most with your readers?

I’ve basically always been a writer, ever since I was a little kid. My first serious foray into writing was a fiction series of about 10 books that I wrote in third grade about snakes. Each book was probably 20 pages long, and I bound them with staples myself. I think it’s safe to say my fiction game peaked early. I’m only just recently getting back into that medium.

I’ve been writing essays about leadership and ‘why I hate giving high-fives’ for some time, but really picked up the pace a few years ago when I was fighting the Air Force assignment system to not send me on a three-year unaccompanied tour while my daughter was actively dying.

At that point that I was either going to fix the assignment issue or end my Air Force career. I started writing about the difficulties I faced and the types of leadership that helped or hindered my efforts to resolve them. Having nothing to lose gave me a reason to keep pushing past gatekeepers and speaking out until the situation was resolved. I wrote about innovating policy, culture-change, and leadership. It quickly became clear that as an NCO and a life-long frustrated innovator, mine was an underrepresented voice that might hold some value.

There have been two particular pieces that really seemed to resonate with the largest number of people. The first was an essay called A Few Thoughts on Air Force Innovation, in which I shared my theory that the Air Force is pursuing innovation by facilitating competition between ideas, when a better approach would be to connect them. The second piece was an article called Keeping Off the Grass, which The Strategy Bridge published. In that article, I described a new way of looking at design and execution of our products, systems, and processes that could bring about continuous innovation and eliminate the cycle of catastrophic failure being the catalyst for change.

A: Why do you think it’s important to upskill and train personnel in more discovery-design methods?

We need to ensure that every one of our people is able to articulate the needs and opportunities they face within their own unique context. Every one of us should probe our particular adjacent-possible for avenues to evolve and innovate. Discovery, in all its various forms, is the process of probing into that dark void to feel out what’s within reach. It’s like echolocation- we can’t really see the possible futures all around us unless we’re bouncing noises off of them; and the environment is always changing, so we should really get used to never not chirping away like bats.

A: There’s no AF-wide solution for that now although I saw quite a few programs and efforts mentioned in your LinkedIn discussion. What kinds of things are you doing locally to move the ball forward? What are you currently working on or towards?

The AF is doing some exciting stuff with training specific solution-development skills into some of the workforce, like agile software development, UX design and data-science. What I discovered is that there are more basic skills in discovery and problem framing that could help Airmen everywhere shine a light within their specific context when highly technical solution development isn’t necessary.

At my last assignment, we began offering discovery, design, and scoping sessions for groups, units, and flights, bringing experience in human centered design and design-thinking, methods like Think Wrong from the company Solve Next, and other practices to facilitate discovery and solution development to whatever their need was. That effort is still going strong, and they’re proving the value of these practices in an operational setting, at multiple tiers. I’ve had the pleasure of leading small groups through workshops in which biases were circumvented, creativity stimulated, and participants connected, collided, and grew ideas collaboratively. These methods could be employed every time we gather to collaborate. Our default approaches to brainstorming, assumption mapping, prioritization, etc. simply don’t work that well.

I’m going to keep writing and pushing my ideas, hopefully luring Air Force leaders into more conversations with experts who could help facilitate the pursuit of what I’m trying to sell here. Hopefully one day I get an opportunity to do the innovation enablement stuff full-time, to help implement these ideas.

A: What is the most challenging part of your work? The most rewarding?

I’d say the most challenging part of my Air Force innovation work is that it’s not my real job. I do what the Air Force wants me to do full-time, and then when they’re not looking, I write articles, offer to facilitate discovery sessions, and host events to try and force discovery where there is no existing process.

The most rewarding part of my efforts is knowing that I’m pushing for a change that will make a big difference in a lot of people’s lives- both personally and in their missions. I’ve had the opportunity to help spark that sense of purpose and empowerment in a few young Airmen, and that’s incredibly rewarding. I always stubbornly pushed to change things despite feeling unempowered, and I got through a lot of moments where I felt too tired to keep pushing. It’s great to help others not have to deal with that.

A: What advice would you have for someone who wants to do something similar?

I think it’s so important to start with being connected. Get involved in a group like the Defense Entrepreneurs Forum, find the wrong-thinkers and design-thinkers on LinkedIn, follow Carmen Medina, Dan Ward, Molly Cain, and all the other government innovation nerds on LI and Twitter. Create connections with like-minded change-makers in other contexts. Become a node yourself. A community can help sustain you in the midst of your inevitable failures- keep close to those who recognize the process as valuable regardless of outcome. It can enable you to benefit from others’ failures, making success exponentially more within reach.

Besides that, my advice would be to read books, engage with a diversity of viewpoints, write, post progress, cry for help, and work out loud for the sake of discovery and so that others might discover from you.

A: Reading any great books now? Any essential reads you would recommend to folks?

I just finished Rita McGrath’s book Seeing Around Corners which I thought was wonderful. It’s mostly about discovery as a way of detecting the weak signals of incoming inflection points and how to navigate them as a business.

I’m reading a book of short stories by Kelly Link right now, as well as the John Green book Turtles All the Way Down (I’ve been listening to his amazing podcast, “The Anthropocene Reviewed” and had to check out his books). I’m enjoying both of those immensely. I’m also on my second read of Chris Beckett’s haunting sci-fi Dark Eden. I think it’s so important to read fiction. Non-fiction is all well and good, but fiction tends to better speak to the human experience. Boiling things down to theories and formulas is a way of limiting reality to make it easier to digest and navigate. That’s very useful, and can be enlightening, but the real truth is in the gross, sweaty, joyful, tragic, and mundane experiences of human beings, not in dynamical shifts measured at a distance. It’s important to mix it up. I think a lot of folks get too caught up in the language of non-fiction and it decouples them from the reality of humanity. Reality is messy and blurry, something that non-fiction often fails to capture.

My essential non-fic on the subject of innovation is in this Goodreads list. I also recently finished Dare to Lead by Brene Brown and would say that’s an essential read on leadership, along with Kim Scott’s Radical Candor. For fiction, some of my favorites are The Three Body Problem series by Cixin Liu and The Girl With All the Gifts by M.R. Carey.

A: For people who are too impatient to read and will likely scroll to the bolded, highlighted, or italicized text – what would you like them to know or walk away from this interview with?

I want people to understand how backwards we still are in our approach to management. We’re failing to train and implement some of the most important leadership competencies and cultural conditions. There is a way to be productive, innovative, fast-moving, resilient, and experience joy in our work; and our current approach isn’t the way to do it.

A: What do you think is next for you – what will Daniel Hulter 2077 be doing?

I’d like to have more time to really get some writing done. I’m barely able to get time for it right now with everything I’ve got going on. I’d really like to get to a place where I am focusing most of my energy on organizational culture and innovation-enablement. I always end up working on that stuff anyways. It would be neat if it wasn’t at the expense of what others think I’m supposed to be doing. I hope to serve out the rest of my Air Force career doing all that I can to facilitate and empower innovation at the level of execution; beyond that is yet to be discovered.

by Aileen Laughlin | Oct 7, 2019 | Uncategorized

Why is being user-centered such a challenge in the DoD?

U.S. Army photo by Pfc. Brooke Davis, Operations Group, National Training Center

I first asked myself this question while working Human Systems Integration (HSI) as a Systems Engineer for a large defense contractor. As I explored this difficult topic, I realized I might have more luck driving change from the other side of the table. So, I made my way to a FFRDC to work more directly with the Government and help shape programs and projects to be more user centered.

Six years later, I’m happy to report that Cyber is the new thorn in everyone’s side! Jokes aside, user-centered design has not yet achieved its full potential. While I’ve seen more programs understand and embrace user-centered design than before, it is still frustrating that so little has changed in the larger environment. Every program I join struggles to bring human-centered practices to bear.

The challenges I most often see: missing or cryptic SOW statements, outdated / incorrect MIL-STDs, insufficient expertise / staff planning, and no or poor requirements. In the worst cases, only a handful of people on the program understand the user’s actual mission, and even fewer have ever spoken with users.

There’s a lot we can learn from commercial industry on this point. Commercial products that succeed tend to have a strong customer-focused value proposition – in DoD terms, they help users accomplish a mission. Delivering a successful product or service requires knowing your customers, the jobs they need to get done, and the associated pain points and gains. That’s true no matter the domain or industry — involvement with users should not be limited to generating requirements. It should not be treated as a contractual checkbox to fulfill, nor as the sole responsibility of an expert or team. Instead, it should be early, frequent, and meaningful. Being user-centric is how the commercial world works because it has an impact on their bottom line. We see this in manufacturing and software alike, where user engagement is a core principle of commercial practices like agile and Lean.

And yes, I understand that traditional DoD acquisition approaches can be limiting. However, it is possible to make designing for and engaging with users a part of how we work. Start by considering these questions:

- If we’re so risk adverse and cost conscious, why aren’t we be making user-centered design a non-negotiable part of our approach?

- Why do we spend SO MUCH TIME writing limiting and insufficient requirements? What might a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) requirements document look like for your program?

- As we read proposals for design and development, shouldn’t we be looking for appropriate expertise and design process-related words like research, prototype, and iterations?

- Why don’t we kick off programs with mandatory visits to engage with users?

- Why don’t we leverage user ingenuity and “field fixes” as valid sources for upgrading systems?

- Why can’t we have multiple user assessments during discovery and design? Why wait until test?

- Why aren’t we inviting or incentivizing or making opportunities for users to be part of engineering teams (e.g., Kessel Run) or directly tapped for ideas and solutions (e.g., AFWERX)?

- In a nutshell, why do we keep doing business this way?

If you haven’t heard, there’s some good news on this front. The AF recently appointed a Chief User Experience Officer. I’m excited to see what that will mean for the Air Force. As an Army Brat, I wish we had named one first. (Call me Army – I want to help Beat Navy!) I’m still holding out hope that the other services will follow suit and, more importantly, that the DoD taking a Warfighter-centric approach to research, engineering, design, acquisition, and sustainment shifts from being novel to our new normal.

by Aileen Laughlin | Sep 9, 2019 | Uncategorized |

If you ask anyone on the ITK team (or really most people I work with), they’ll tell you I am always sharing articles. I recently came across this article about one person’s progression from sweeping floors to executive leadership, and instead of just emailing it to some friends I thought I’d write about it for the ITK blog.

The article appeared in Inc magazine, and it’s titled This Kombucha CEO Hired a Man Who Spoke No English. He Is Now a Company Executive. It’s a terrific story about solving problems and working together – two big themes of Team Toolkit’s work.

The article is a great example of how having the right attitude can take you far in life. However, I really enjoyed imagining this gentleman’s humility, curiosity, desire to learn, and develop mastery as he progressed through different areas within the company. The CEO’s comment about generalist vs. expert and how despite not having a laundry list of degrees, this employee is always the first to solve a problem made so much sense! Openness and diversity in thought and experience are such important elements of solving problems and practicing innovation.

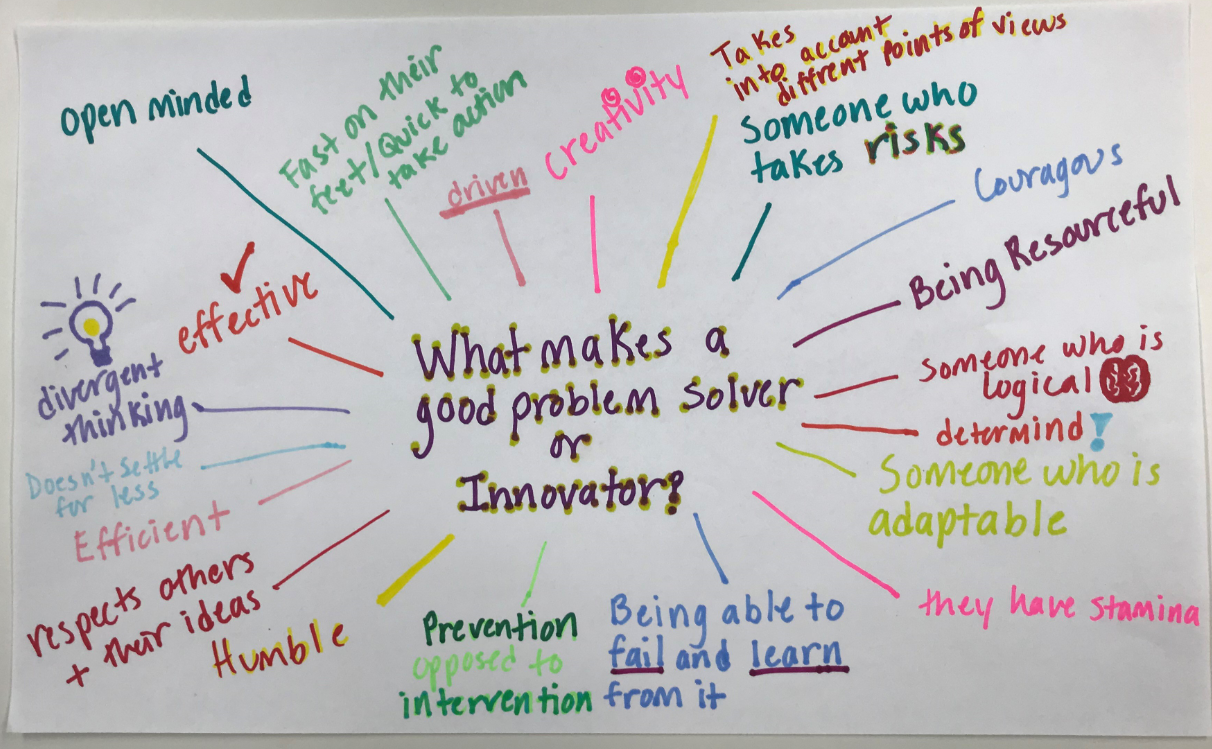

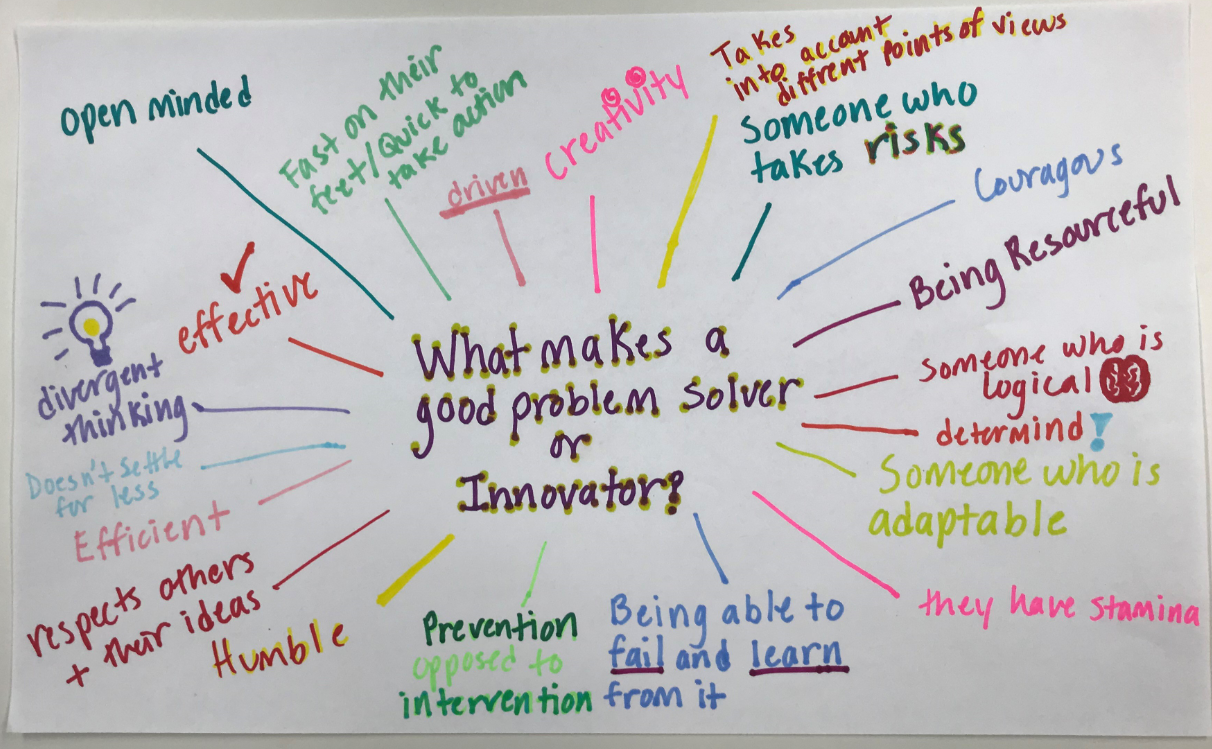

Team Toolkit thinks about this stuff a lot, and we’re always exploring ways to better understand it. At a recent event, we took a post-it poll asking, “What makes a good problem solver or innovator?” Our high-school intern, Niomi Martinez, turned the poll results into the Mindmap above.

We’d love to hear what you think – Anything missing from the list? Anything you agree with? Disagree with? Share your thoughts in the comments section below!

MITRE employees are not afraid to fail. They recognize the growth and learning that comes with – one employee said, “if not for this failure, I wouldn’t be here at MITRE”.

MITRE employees are not afraid to fail. They recognize the growth and learning that comes with – one employee said, “if not for this failure, I wouldn’t be here at MITRE”.