I once listened to a city council meeting where one party was seeking exception to a rule. Other parties opposed the notion of such an exception, arguing it negatively impacted their lives. Residents and Council Members shared their thoughts. Some supported the exception, some did not. One Council Member gave an elaborate explanation of why the exception was the right thing to do, highlighting benefits to the public and effectively validating the arguments of the supportive party. Surprisingly, he then said he couldn’t support the exception.

He cited the law which, unless changed, clearly and effectively stated it couldn’t move forward. As I recall, others seemed to agree, even if begrudgingly. The meeting soon ended, and that was that. What had this council member done? He’d started by focusing positive aspects for the idea, validating and perhaps even empathizing. Couldn’t he have skipped all that, opening by citing the law? Yes, but those present might have had a very different experience.

Is focusing on problems inherently negative? I don’t think so. If we avoided anything negative, controversial, or potentially offensive, how would we learn, grow, and progress? The MITRE Innovation Toolkit Problem Framing and Rose, Bud, Thorn activities, for example, give permission to have difficult conversations about what’s going wrong, what’s going right, and opportunities for improvement.

When facilitated correctly, these hope-centric tools can be used in a space where participants feel safe, free to share their thoughts, and with an underlying theme that things will get better because of it! Like the council member described above, these tools can give people a chance to highlight the positives and negatives of a given situation.

People understandably become invested as the outcomes might directly impact their lives. They might become defensive, resistant to change, and even oppositional. I previously wrote an article, What Still Works, offering that by focusing on the things that work, we can sometimes deduce what’s actually wrong. In this article, I want to offer that in addition to identifying that which is broken, spending time thinking about what is right can also disarm, dissuade, and draft.

Disarm

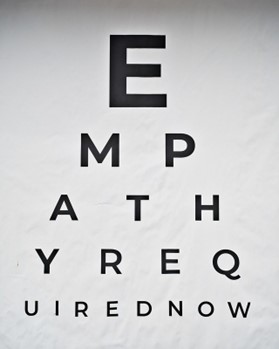

People have opinions. That’s something to celebrate! What if you want people to have the same opinion on a given topic? Anyone who has tried to create such a reality knows how difficult it can be. One method is to explain what you think the correct opinion is, and then to tell everyone else they are wrong. You might not get any awards in resolving conflict, but an approach it remains. What if you started by highlighting the merits of both opinions? Like any conflict between two or more parties, starting with genuine empathy goes a long, long way. It might even disarm what could otherwise be a defensive party.

Dissuade

With defenses down, people might be willing to hear opposing viewpoints. If empathy, kindness, understanding, and acknowledgement of the positive aspects of others’ opinions continue, it could dissuade further negative actions and start paving a path for progress.

Draft

Feeling validated goes a long way. Validation might be the single most overlooked gift that can keep on giving. Asking oneself, “why might they feel that way?” or better yet, “have I ever felt that way?” is the beginning of real, positive change. Not only might an opposing party be disarmed from defensiveness and dissuaded from close mindedness, but they might also start seeing alternate viewpoints. At risk of using sports terminology incorrectly, perhaps someone might be drafted to a new team.

Focusing on what others are doing right, in addition to what they might improve upon, creates an empathetic space where both parties can feel validated. What do you lose by giving away such a gift?